For the last few months I’ve been writing and researching a topic near and dear to my heart. The year of 1989 looms large in my moviegoing history and I wanted to put this year into intense focus in a longer format. I began working on this book called, tentatively, The Summer of 1989: The Last, Greatest Hollywood Summer in March and I’m just getting to the chapters on individual movies. The following post contains a portion of what I’m calling “The Preamble.” The opening chapters that set the 1989 stage, focusing on the state of the industry and discuss some of the films that don’t technically fall under the auspices of “Summer” but certainly inform the movies to come.

If you have comments, I’d love to hear them. I’ve spent enough time in the echo chamber. I just needed to poke my head out for a spell and test the air. Please enjoy this small section (that probably won’t exist in the manuscript in any form quite like this because early drafts!) while I wait for responses from publishers and agents regarding my manuscript prospectus. The fun part!

“The Preamble” Part 3: Last, Greatest Hollywood Summer Begins (Almost)

When discussing the greatness of the cinematic year of 1989, it’s all too easy to get lost among box office sensations and high-profile sequels. If 1989 were a movie it would be King Kong vs. Godzilla vs. Mothra vs. Rodan starring Batman and Indiana Jones and Riggs and Murtaugh. That’s an awkward metaphor – can I get a redo? Never mind. Everything just came up kaiju on my doodle sheet anyway.

When I piled up my stack of movies and rewatches for this meditation on the last, greatest Hollywood summer, I looked forward to having excuses to show my daughters Batman and The Last Crusade, but I craved the time I would carve out to watch the supposedly lesser films that made 1989 the complete entertainment package. Films like Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, The ‘Burbs, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, Troop Beverly Hills, and Heathers represented widely varying degrees of contemporaneous success and notoriety, but all have endured as testaments to the ways in which Hollywood (and its periphery) dared to entertain us when it seemed like they didn’t have anything to lose.

With Rain Man topping the Box office until February that left little room for new releases to catch fire. 1989 wouldn’t boast a $10million opening weekend until The ‘Burbs on February 20th, a release that also comes with the 4-day weekend asterisk.

Pop quiz: Was Joe Dante’s The ‘Burbs was a successful film?

Since my schedule didn’t permit me sitting next to you while you read this particular chapter, I’m going to assume you’re telling me, “No! Obviously not. Please make these questions harder so I don’t lose interest in your quizzy little book.” That’s harsh, but fair – but I want to highlight The ‘Burbs specifically because Dante’s slice of black humor represents a small, but important aspect of 1989’s output. Also, pop quizzes keep you on your toes.

Regarding The ‘Burbs Gene Siskel offered, “The script would like to be a horror film, a comedy and a commentary on suburban living, but it doesn’t hit any target.” The LA Times’ Kevin Thomas called it a “grimly unfunny comedy,” an “endlessly labored spectacle” with “no discernible point…” Vincent Canby, my favorite critical curmudgeon warned that The ‘Burbs was “as empty as something can be without creating a vacuum.” All those famous guys just corroborated your assertion that The ‘Burbs failed. Time to move on to discuss Richard Corliss’ assertion that The Adventures of Baron Munchausen reeks of “corporate flop sweat.” (Those kooky film critics strike again!) But check your rage for just a moment.

Like most black comedies, critics and audiences can’t always tune into the right bandwidth. Time and time again Hollywood has proven incapable of selling or packaging dark comedies in such a fashion as to inspire attendance. As a genre, they’re largely reliant on tone and performance rather than set pieces and out-of-context quotable humor. I’d go as far as suggesting that the average cinema attendee can’t even define or list movies that successfully fall under the category. If you Google “black comedy,” the search spits back some obviously acceptable entries like Heathers, but also includes Kick-Ass, Hot Fuzz, and Birdman. It’s no wonder that John and Jane Q. Netflixer can’t adequately receive the stylistic language of gallows humor when not even Google can adequately supply a decent list of proper examples.

Though the black humor format can be traced back to Aristophanes, it’s Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” that’s probably the most known early example. In it, Swift (tongue firmly in cheek) declares that in order to solve both the problems of hunger and overpopulation, we should start eating all the extra babies. When I first read that piece in high school, a switch flipped. Now that’s dark humor!

In his book American Dark Comedy: Beyond Satire, Wes D. Gehring coalesces Darwin and Freud into his dark comedy origin story. He says that comedy is both a defense mechanism against inevitable death (from Freud) and the recognition that life is nothing more than a haphazard series of luck in the form of evolution (Darwin). The surrealism of the form suggests an externalization of all of this subconscious grappling with deep thoughts.

The existential philosophers Sartre and Heidegger loom large over humor derived from our godless, irrational world in which we cannot depend on other humans and anguish is a universal phenomenon. Funny, right? Look no further than that wholesome All-American director Frank Capra who said his own Arsenic and Old Lace was a demonstration of the fact that comedy and tragedy are so closely aligned it doesn’t take much of a push to “send the dramatic see-saw from tears to giggles and back again.” In case you need a refresher, in Arsenic and Old Lace, a pair of old Brooklyn biddies poison lonely elderly men with elderberry wine and arsenic and their nephew (who believes himself to be Teddy Roosevelt) buries the bodies in the cellar to stop the spread of Yellow fever. Arsenic, The ‘Burbs and Heathers (which wasn’t even given the decency of a proper theatrical release) share the same DNA, although the latter films paint their humoristic black wordplay with horror movie tropes to further punctuate the tragedies.

American humorist Brian P. Cleary perfectly captured the nature of dark humor when he said, “A good friend will help you plant your tulips. A great friend will help you plant a gun on the unarmed intruder you just shot.” Let’s translate Cleary’s statement into cinematic terms. “A good friend will help you plant your tulips” equals romantic comedy or period drama. Memoirs of a Geisha (2005) features a scene of cultural and romantic significance beneath a cherry blossom tree. Self-defense against an intruder recalls any number of thriller or horror films (Wait Until Dark, Dial M for Murder, Halloween, etc.), but black comedy is the scene where two friends flounder through the maneuverings of planting a gun on the supposed intruder’s turgid corpse. You and your comically inept friend become the murderous anti-heroes or heroines of your own story. Now that’s black humor!

But about the question of The ‘Burbs’ success or lack thereof. Critics found little consensus but largely throttled it. Audiences came to see Joe Dante’s film as the Tom Hanks flop that temporarily curtailed his soaring career in the wake of Big (1988). A quick look at the box office numbers suggests a slightly different reality. The $18 million movie made back twice its budget at the domestic box office and $49.1 million internationally. While far short of success, it’s hardly the bomb hearsay has led us to believe. The ‘Burbs opened strong, courtesy of Tom Hanks’ emergent stardom, but tailed off quickly thereafter.

Joe Dante has had a long and successful moviemaking career and he’ll always be most widely known for Gremlins, but I’d argue that The ‘Burbs inspires his most devoted fans, reacting according to Newton’s Third Law. For every negative reaction about The ‘Burbs there is an equal and opposite reaction. About the film, he said in an interview for the website of the Toronto International Film Festival, “It was roundly vilified when it came out, but it seems to have weathered quite well.”

The ‘Burbs represents a quintessential cult film experience. Maligned and misunderstood at the time of its release, Dante’s film shoehorned cannibalism, demonology, and body snatching into mainstream cinema under the guise suburban slapstick starring new Hollywood darling Tom Hanks. Five years prior, that Hanksian charm had shepherded a coke-snorting donkey to a $40 million domestic box office share, so none of this should come as much of a shock. After the success of Big, the actor responded with a series of eccentric choices not befitting a newly anointed box office wonder boy, including, in order of release, Punchline, The ‘Burbs, Turner & Hooch, Joe Versus the Volcano, and Bonfire of the Vanities.

For The ‘Burbs, however, those Hankspectations proved damning. These Big fans, irrationally charmed by the face-value creepiness of a 28-year-old Elizabeth Perkins knowingly having sex with a pubescent boy, flocked to The ‘Burbs and found their expectations for wholesome family entertainment put through the wood chopper. Mainstream audiences are nothing if not short on memory and attention span. Cult movies that come through the Hollywood system happen largely as a result of unmet expectation. Good – even great – movies suffer the misapplied judgment of audiences and critics that come face to face with a movie they just can’t quite wrap their heads around. The term “cult” applies to movies of all shapes, genres and abilities – but glossy, high functioning cult movies from within the studio system arise because people get swept into a movie for reasons other than the movie itself. Those initial reactions shape the expectations of others, including those who might have otherwise viewed the film on its own terms.

It wasn’t too long ago that the box office life of a movie depended on more than an opening weekend. Raiders of the Lost Ark, for example, became a huge hit for Paramount despite their inability to advance market the film. In Blockbuster: How Hollywood Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Summer, Tom Shone says, “…and while the film would eventually take in $209 million, more than any film in Paramount’s history until that point, it did so under its own steam and in its own time, chugging around at the $1.5 million-a-week mark for the best part of the next year…” Raiders of the Lost Ark made only $8 million during its opening weekend. To consider just how much had changed in the eight years between the release of Raiders and The ‘Burbs, Joe Dante’s film made $11 million in its first weekend, but was booted from theaters after five weeks, dubbed an immediate critical and commercial failure.

Patience waned for a couple of reasons. Even though there were more theater screens on which to play, more movies were being released overall. Fewer movies were released in June of 1981 (prime movie season) than were released in February of 1989. Secondly, the home video release window had continued to narrow – but not just due to the business of rentals. With sell-through movies becoming increasingly more common, studios rushed their biggest hits out of theaters to capitalize on home video demand. Likewise, exhibitors rushed slagging performers out of theaters to decrease competition for presumed successful enterprises. Raiders of the Lost Ark would never had had the opportunity to hang around in theaters for more than a year making in the neighborhood of $1.5-2 million per week. It would have been ushered onto sell-through home video, thus clearing the path for another movie to open big and disappear in a matter of weeks. In March of 1982 after 10 months in theaters, Raiders still played on more than 600 screens.

Even though the winds of change had started to reconfigure the cinematic landscape, some movies still managed to take the market by storm, if only on a smaller scale. Released on February 17, 1989, a little Orion Pictures teen comedy arrived in 1,196 theaters across the United States. Critics had panned the film. It starred a 25-year-old actor who’d last appeared in a supporting role in Stephen Frears’ Dangerous Liaisons and a 24-year-old tertiary Lost Boy.

I didn’t have the pleasure of seeing Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure in the cinema. It snuck into February cinemas with little marketing, when most movies appeared in theaters as an afterthought – yet this critically panned teen comedy about California dimwits landed a $6 million opening weekend, placing third behind The ‘Burbs and Rain Man in its tenth week. Unlike The ‘Burbs, however, Bill & Ted expanded. In the following weeks it earned $5.6 million, $5.5 million and $4.2 million and remained in the Top 10 for 8 weeks.

Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure represents the pinnacle of the 1980’s filmmaking modus operandi. An inherently absurd high-concept that falls apart after any amount of scrutiny – yet the viewer’s too entertained by the movie’s pure joy of existence (and puerile historical gags and references) to bother with anything as tedious as how Bill and Ted irrevocably rewrite history by creating a bromance between Socrates and Billy the Kid… or how an entire high school career hinged on a single oral history report. 1980s-based screenwriters built careers on such arbitrary squad goals.

The film also – and this is perhaps the most important aspect of Bill & Ted’s success – celebrates positivity rather than sneering derisively at its title characters’ inferior intellect. Consider the fundamentally different approaches between Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure and something like Dude, Where’s My Car? (2000), a certain Bill & Ted descendant.

Despite their slacker wrapping, Bill S. Preston Esquire and Ted Theodore Logan have been given agency that turns caricatures into fully rendered and relatable humans. A movie in which two failures (in the near future) have already saved the world with the power of a transcendent guitar riff – but first have to overcome the minor hurdle of getting an A+ in an oral History exam by traveling back in time to collect figures of historical interest. It’s like borrowing the 1927 Yankees to win your kickball game – if upon that kickball game the fate of the world rested. If you spend too much time dissecting the time travel mechanics you will pull back the curtains on Oz and dissolve the magic that makes Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure standout among dozens of other dimwitted teenage comedies.

Contemporaneous critics struggled with Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure. As Chris Williams of the LA Times wrote, they saw “a glorification of dumbness for dumbnesses’ sake.” The New York Times’ Vincent Canby called it “painfully inept.” The Washington Post’s Hal Hinson: “undernourished.”

Critics don’t get a pass just because they’ve been given a soapbox with millions of listeners. I’ve had my own soapbox, albeit a much smaller one, and I chose to walk away after a couple of years because the job of being a critic sucked the joy out of moviegoing. The job of a critic is to watch a movie and find fault – naturally that leads to rampant negativity and self-loathing. (I added the self-loathing part because if you hated Bill & Ted I assume there’s some self-loathing present.) I found reasons to dislike all movies and celebrate few. Dumb characters in a high-concept movie full of logic gaps and impossible (not just improbably) scenarios necessitates the abuse of the killjoy hammer.

How often have you read a critical film appraisal that acknowledged a narrative fails most standard litmus tests, but just works because it’s a damn good time? (Whenever it happens, I assume the critic in question had a healthy dose of painkillers before his private viewing.) Can you ever imagine Bosley Crowther admitting he had a ripping good time at a movie?

Moviegoers, however, have not been saddled with the onus of specific scrutiny at the expense of their entertainment. Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, like the best of the pure entertainment 1980’s, presents a fantasy version of the real world unblemished by physical, grinding realities. The characters’ intelligence doesn’t post an artificial barrier to their success. In many instances stupid characters arrest the narrative as the result of an inability to move the plot forward. Momentum occurs despite their lack of agency. Keanu Reeves and Alex Winter boast tremendous on-screen chemistry, as if they’re acting as displaced halves of the same brain. You could analyze Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure from dozens of different directions, but the success of the film relies on this synergy.

Though lacking in book smarts (Caesar will always remain “a salad dressing dude[1]”), Bill and Ted demonstrate quick wits and even an ability to manipulate the logic of the film, thereby outsmarting the viewer that’s assured himself of his superior intelligence because he knows an actual thing or two about Napoleon. The most magnificent moment in the film undermines that supposed viewer superiority.

Early in Excellent Adventure, Ted’s dad asked Ted about the missing keys[2], but the boys have no clue as to their whereabouts. Later, when Bill and Ted need to rescue their historical figures from jail, they wish they had those very same keys.

After a pensive moment, Bill exclaims, “If only we go back in time to when he had them and steal them then.”

“Well, why can’t we?” Ted asks, further suggesting that after the report, they’ll go back in time, steal the keys and put them outside the police station.

Presto! The keys appear, as if by magic behind the very same sign – but it’s not technically magic (movie magic, maybe) – it’s our “dumb” characters riffing on the physical laws of the time-travel film and manipulating audience expectation. They might not know how to pronounce “Socrates” correctly, but they’re clever enough in a crisis to manipulate time and space.

“Hey! It was me who stole my dad’s keys!” Ted gleefully exclaims.

When I revisited Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure for the first time in many years for this chapter, I worried it wasn’t going to hold the same spell over me. I found myself dissecting the movie to see what held it all together. I focused on the time travel fallacies and questioned why any of it worked at all. It still didn’t matter.

I found myself drawn to the ways the movie knowingly manipulated the audience. Arriving in theaters months before the release of Back to the Future II certainly helped. Once Back to the Future II began diagramming parallel timelines and warning about time paradoxes, Bill and Ted might have had a harder time casually solving their own conundrums with the pinky promise of future time travel. The scene with the keys, for example, or the early meeting of the two pairs of Bill and Teds (which according to Back to the Future’s laws might make the universe implode). Unlike those testy critics, a viewer will only care to pick apart a narrative if they’re not entertained to distraction. Pure entertainment doesn’t require the “how” or the “why;” it just requires a willing ignorance, an embrace of our own dumbness as viewers. With regard to Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, I’m happy to glorify my own dumbness if it means I can still experience childlike enjoyment while watching movies.

The face-value absurdity of Joan of Arc commandeering an aerobics class or Genghis Khan attacking a sporting goods store on a skateboard, Beethoven simultaneously tickling two electric keyboards. Napoleon throwing a tantrum at a water park called Waterloo. These remain simple, bordering upon lazy gags – albeit lazy gags graced with rapid-fire abundance and an ingenious high-concept wrapper.

Director Stephen Herek had a solid, but unsung movie career before the studios got ahold of talents and ushered him into routine, forgettable fare. He began his career with Critters, Bill & Ted, Don’t Tell Mom the Babysitter’s Dead and The Mighty Ducks (all crowd pleasers) before taking on more “grown-up” films like Mr. Holland’s Opus, Rock Star and Holy Man. The pace of those so-called dumb entertainment movies just agreed with him. Not every filmmaker treats populist or “dumb” entertainment with the kind of respect required for two idiot savants to turn the tables.

Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure cost $10 million in 1989 and returned $40 million, $9 million less than The ‘Burbs. Each returned $30 million dollars above production budget. When was the last time you heard someone call Bill & Ted a box office bomb? Still not bad for two idiot teens from San Dimas, California that surprised us all with a deceptively smart, super dumb movie back in 1989. Perception and expectation shapes the legacy of any movie. Those initial responses can take generations to overcome.

And now you’re probably asking, “But didn’t you mention that stone cold classic Heathers way back in the beginning of this tirade?” I did. I’m so glad you asked. What was your impression of Heathers back in 1989? Did you love it like everyone else did? More quizzes!

Trick question.

Nobody saw Heathers in the theater. If you did, I congratulate you on your incredible luck (proximate residence to one of the few theaters screening it) and foresight (you went! Good for you!), which stands head and shoulders above my feat of seeing UHF twice theatrically. Heathers appeared on only 35 screens in the U.S. on March 31st, 1989, making a total of $263,000 in its first week of release. And it’s not as if New World had prepared a word of mouth grassroots campaign to boost business. The movie dropped down to 26 theaters the subsequent week – even though its per theater average remained higher than anything except the box office champion Major League. In five weeks of release, the $3 million Heathers grossed slightly more than $1 million.

Despite good word of mouth and reviews, New World failed to provide any kind of promotional push. Calling Heathers a failure based on box office numbers would be a disservice. It didn’t even have the opportunity to fail. It’s not a very telling comparison, but one I’ll dare to make anyway. Heathers made more per screen in its opening week than every 1989 weekly box office winner until Pet Sematary on April 21. Box office numbers rely on so many factors outside a movie’s control that it’s a futile statistic with which to judge merit – but it is useful when considering trends, marketing efficacy and studio ineptitude. New World wasn’t just inept – it was bankrupt. But it did own Marvel Comics as one lovely feather in its cap.

Co-founded by Roger Corman and his brother Gene in 1970 (following their departure from AIP), New World Pictures, Ltd. became the last national low-budget film distributor. Devoted to making low-budget films by new talent, New World launched the careers of Jonathan Demme, Jonathan Kaplan, Ron Howard, Paul Bartel and everybody’s favorite Joe Dante. They also acted as the U.S. distributor for foreign films from Ingmar Bergman, Fellini and Kurosawa. In 1984, the company split into New World International, New World Television and New World Video – the purposes of which should all be pretty self-explanatory. In 1986, they acquired Marvel Entertainment Group, the parent company of Marvel Comics.

In 1988, the same year that New World premiered a little film called Heathers in Italy (obviously), the company fended off Chapter 11. In 1989, New World began selling itself piecemeal to investors. Would Heathers have become a box office hit with full studio support? I enjoy the hypotheticals as much as the next fellow, but it’s hard to see Heathers getting studio backing – even in the fairly free-spirited 1989.

By the time I became aware of Heathers it had already become a VHS success story. Heather never registered as a failure, like similarly untoward The ‘Burbs for example, because it hadn’t appeared on anyone’s pop culture radar. Consequently, it didn’t have that stigma to overcome. When teenagers discovered it on VHS many moons later, Christian Slater and Winona Ryder had become teen attractions, wall-posters but not box office darlings of a Hanksian magnitude. It appeared in video stores as if by magic, free of expectations based on box office performance or critical derision. It became an important personal discovery to everyone that picked up on that VHS box on a whim.

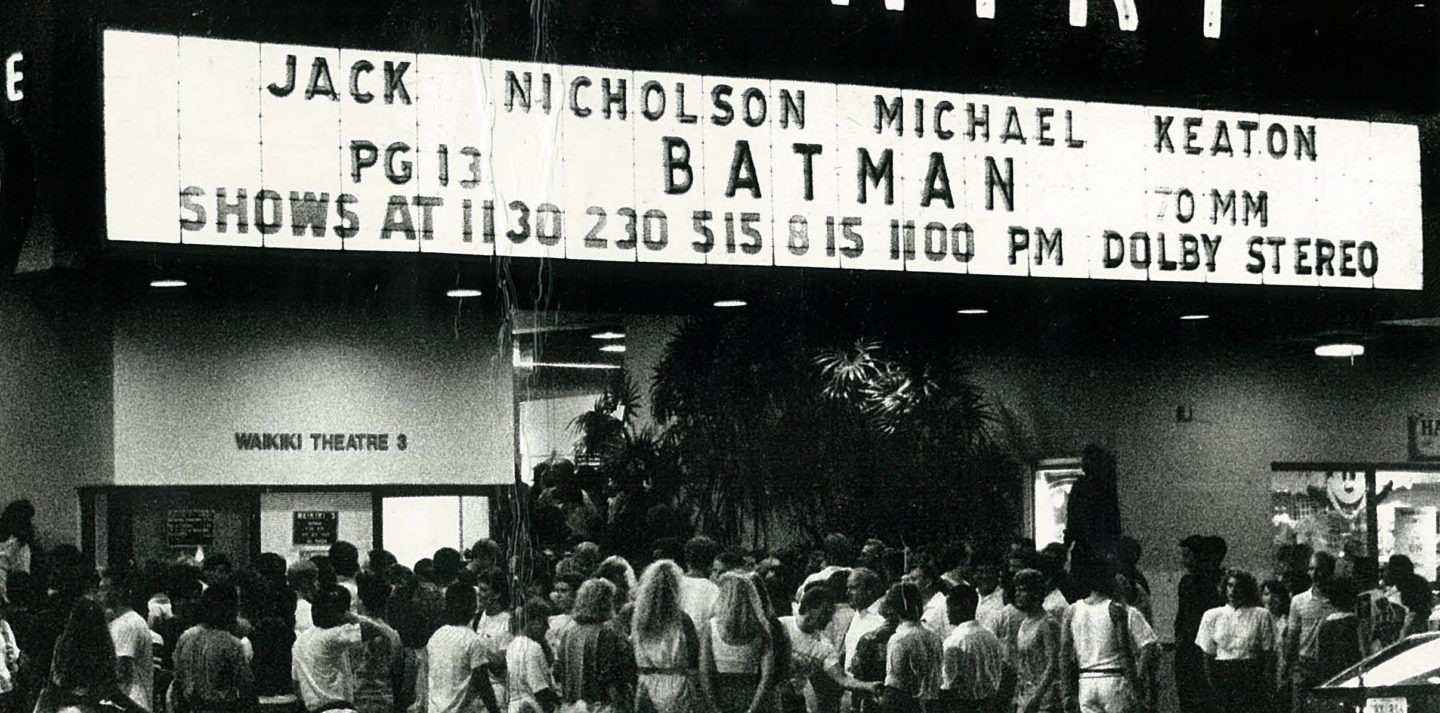

While the summer of 1989 felt positively flooded with blockbusters and box office success, the full picture of 1989 only comes into focus with the inclusion of the little movies that found life on in later years on VHS, the box office flops, the big-budget franchise disasters and curiosities, the dark little comedies that succeeded despite themselves. We all knew something was coming because Warner Bros. had been pumping Batman down our throats for months already, but movie audiences felt more than just the rumble of the Batmobile. Everything felt a little unsettled and no matter what happened — we weren’t going to look away.

[1] For years I heard this line as “solid dressing dude,” and honestly this works just as well as “salad dressing dude” because that Roman toga really does offer a certain untapped appeal as an alternative to my day-to-day wardrobe of jeans and a t-shirt (hoodie, weather dependent).

[2] Chekhov’s missing keys.

I’ve spent time writing about many of the movies I’ve been viewing in my #Watch1989 marathon. Maybe you’d like to read some of those instead:

1989 Flashback: Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure

1989 Flashback: The Experts

1989 Flashback: Skin Deep

1989 Flashback: The Dream Team

1989 Flashback: Kinjite: Forbidden Subjects

1989 Flashback: Gleaming the Cube