#12. The Legend of Hell House (1973)

Nature of Shame:

Nature of Shame:

Unwatched Blu-ray, I suppose. I needed a semi-scary spook flick for my wife and sister-in-law who aren’t “down for anything,” contrary to their claims.

Hooptober Challenge Checklist:

Decade: 1970’s

A couple years ago, I made these non-horror-watching hooligans watch John Carpenter’s The Fog. They still talk about The Fog and I’ve struggled to repeat that performance. This year I presented Night of the Comet, Night of the Creeps and The Legend of Hell House as possible viewings. Much to my surprise, they picked Hell House. So here we go.

The Legend of Hell House Elevator Pitch

An eccentric millionaire hires a physicist to prove life after death by sending him into the Belasco House, “the Mount Everest of haunted houses,” for a week. He brings along his wife, two mediums and unbridled skepticism.

In the Haunted House of Bloody Narcissism

I last watched The Legend of Hell House many years ago by myself in an old Boston apartment. My wife was in law school and I spent many nights up alone watching movies. It spooked me a little bit. Not Session 9-level turn-on-all-the-lights-and-invite-every-living-person-over-for-a-nightcap grade spooked, but unnerved nonetheless.

Upon this viewing, perhaps because of the mixed company (read: any company), I paid as much attention to the reactions of the viewers as my own tingler.

Based on Richard Matheson’s Hell House, The Legend of Hell House wasn’t the super straight A-to-Z ghost story and retelling of the Shirley Jackson novel that I remembered. Due in large part to Roddy McDowall, the film serves up just enough light comic relief to dull the overall fright factor. Some of it seems rather silly, like 2018’s imitation of a traditional 1970’s horror movie. This makes it a very strong choice for someone looking to dip their toe into the deeper waters of horror. The tenor and pacing of the 70’s might create distance in a viewer more accustomed to modern cinematic conventions.

So. Uh. You Mentioned Ghosts?

This is no Scooby-Doo pull-off-the-sheet style “haunted” house tale. Although Dr. Lionel Barrett (Clive Revill) dismissed the possibility of life after death as a self-induced psychological manifestation, there’s no part of you, as the viewer, that sides with the skeptical doctor. It’s clear from the beginning of this film that Dr. Lionel is going to get these people killed. The only question — as Roddy McDowell suggests — is how many.

Director John Hough uses gloomy skies, minor keys and ominous daily time stamps create a mood. The music (or lack thereof) contributes most effectively to this mood as there’s no sonic distinction made between the score or ambient sound effects. They are one and the same.

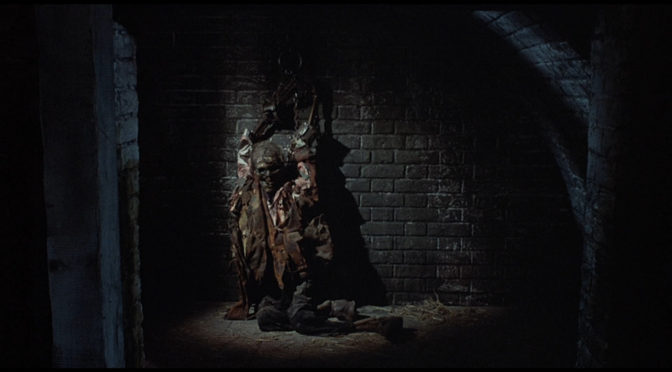

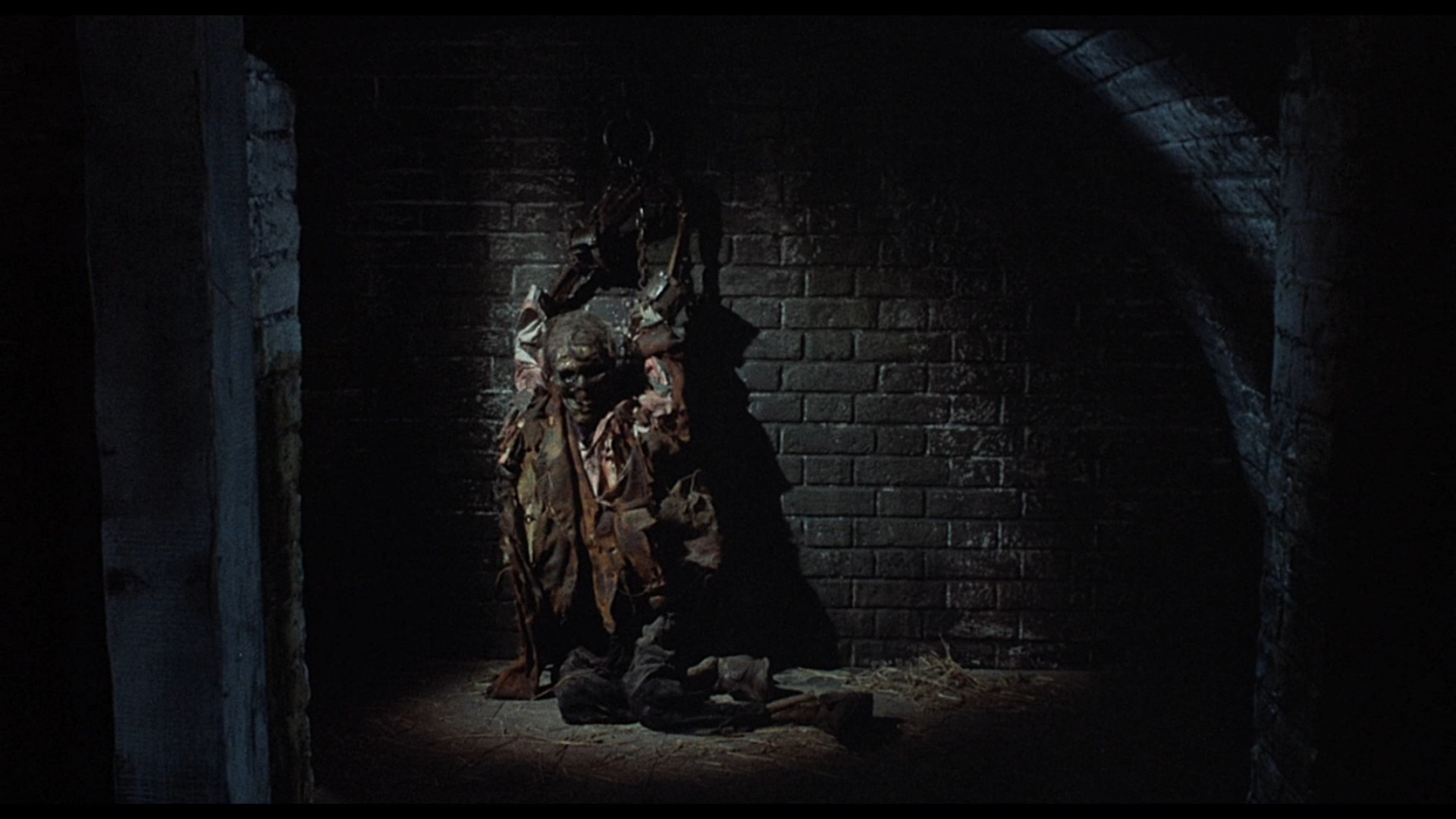

The house blocks out all incoming light. The rooms, cluttered and claustrophobic, convey a sense of the owner’s (and suspected haunt’s) personality without ever giving Emeric Balasco a voice. Set design and lighting suggest his voice, his backstory. As the team digs further into the history of Balasco, the sordid and previously latent details become revealed.

If not for McDowall’s eccentric medium, Benjamin Franklin Fischer, The Legend of Hell House might have been too straight, too sinister. Even though Ben’s the most scarred of the characters in the film (he’s been through this experience before), Roddy McDowall can’t help but inject affability into his performances. He’s a broken man, but his nervous energy provides relief from the stoic seriousness.

Ghosts Can Kinda Die! #SpoilerAlert

Since the audience knows the truth that Dr. Barrett seeks, The Legend of Hell House’s mystery becomes not whether the house is haunted, but who’s actually doing the haunting. We’re given the run around by the sordid spook(s) inhabiting Belasco House.

Dr. Barrett becomes the target of particular rage. His wife Ann goes on midnight lust walks and demands sex from Ben. The mental medium Florence Tanner (Pamela Franklin) has ghost sex. When Ben finally opens himself up to receive the ghost transmissions, we’re relieved to finally get some answers (which confirm our suspicions all along).

That said, the mystery isn’t entirely effective. Confirmation allows us to focus back on what works so well in The Legend of Hell House. Mood. The traditional haunted house scares of Hell House work because they’re back up by delicious production design and a singular focus on low-level tension. With each passing day the veracity of the ghost’s behavior increases. With each new timestamp our own expectation for violence grows.

Arguably the actual events don’t even live up to our anticipation of the events. Anticipation fuels almost all of the horror in The Legend of Hell House. The curation of expectation of what might happen leads us from narrative beat to narrative beat. The best horror films understand how to build this tension so that the actual horror event serves only to punctuate the anticipation. Bad horror films focus too much on the horrific elements themselves. A punchline without the setup.

Final The Legend of Hell House Thoughts

Delivers moderate scares — and would certainly work as an introduction to another level of horror film. The Legend of Hell House finds its groove and rides it to a conclusion. Some, including those in my viewing party, felt that the ultimate payoff felt underwhelming. True. The Legend of Hell House lacks the proper payoff of other, better haunted house films like The Haunting, which parallels this film in more ways than one.

I don’t necessarily agree that it undermines the film, but I understand the point. The ending’s a bit bonkers at face value. I won’t spoil the final scene for anyone idly checking in on my 31 Days of Horror progress, but suffice to say that the film concludes with a bizarro twist of character. If you let it simmer, however, I think you’ll warm to my idea that it’s an abstractly disturbing moment of humanization. It speaks to the power of myth and legend — the power of a deranged man to endure long after his death.

The Legend of Hell House Rating:

Availability:

Shout Factory released an excellent Blu-ray of The Legend of Hell House back in 2014.

Some scenes look rather soft, but Hough used so much soft focus and diffusion filters throughout the film that I’d be surprised if the film *could* look better than this. The film grain remains and looks remarkably natural.

2018 @CinemaShame / Hooptober Progress

#1. Deep Rising (1998)

#2. The Mist (2007)

#3. Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (1948)

#4. Abbott and Costello Meet the Invisible Man (1951)

#5. Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy (1955)

#6. Maniac Cop (1988)

#7. Nightbreed (1990)

#8. The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959)

#9. In the Castle of Bloody Desires (1968)

#10. Chopping Mall (1986)

#11. The Kiss of the Vampire (1963)

#12. The Legend of Hell House (1973)

James David Patrick is a writer. He’s written just about everything at some point or another. Add this nonsense to the list. Follow his blog at www.thirtyhertzrumble.com and find him on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.