Welcome, Backstage Blogathonners! And a special thanks to our hosts Movies Silently and Sister Celluloid. This is my tardy entry that was written and stored away in December, waiting for the blogothon dates to arrive… and yada yada yada… I completely forgot to post the thing. Better early and late at the same time than never.

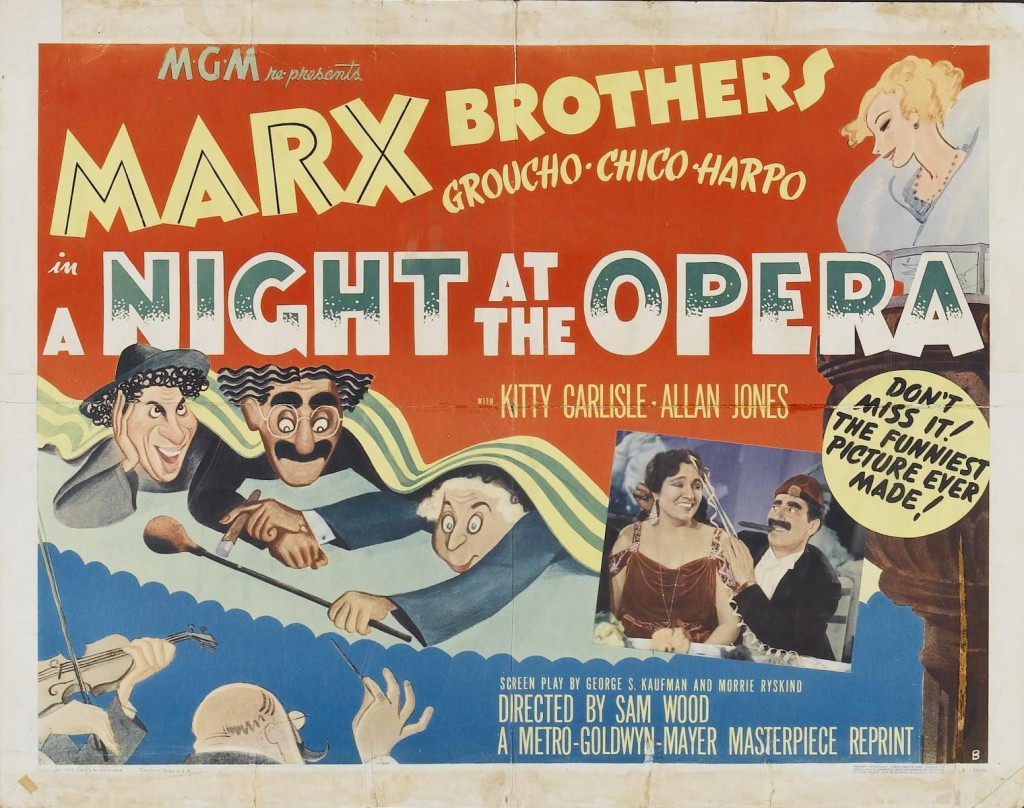

Backstage at A Night at the Opera

Research has proven that the Marx Brothers have turned more people into classic movie fans than any other act in show business. There are pie charts and Venn diagrams to back this theory. It’s fact. Incontrovertible. Contained on certified documents stored in the vaults of the First National Bank of Freedonia.

I couldn’t have been more than six or seven when my parents first showed me a Marx Brothers movie – Animal Crackers. The result? A lifelong love affair with classic cinema. Well, I attribute that to the Marx Brothers and a whole bunch of Universal horror flicks I devoured one special Halloween. Special props to The Invisible Man.

At such a tender, innocent age, I couldn’t fully grasp Groucho’s wordplay or keep up with Chico as he sparred, in staccato fits and spurts. No matter how much I consciously understood, the Marx Brothers enchanted me through physical comedy and dialogue with the rhythm and unpredictability of a great jazz improvisation. Though I eventually grew to understand the finer linguistic machinations of Groucho’s acerbic wit, the brothers Marx were always immediately accessible. I’m embarrassed to admit, however, that it would be years before I realized Groucho’s mustache was actually *gasp* painted on. I was slow on the take there.

“When I invite a woman to dinner I expect her to look at my face. That’s the price she has to pay.”

Groucho’s opening volley from A Night at the Opera. A woman waits (Margaret Dumont, of course, reprising her role as Groucho’s favorite punching bag), impatiently, for her date to arrive. Her date is Groucho and Groucho has spent the entire lavish meal dining right behind her. Similarly, when I first considered subjects for the Backstage Blogathon I couldn’t think of a movie from the sub-genre that drove me to verbosity. But then it hit me, like the realization that Groucho had been sitting right behind me all along.

As I said, A Night at the Opera wasn’t my first Marx Brothers’ film. It’s not even my favorite (it’s hard to argue with the brilliance of Duck Soup in this category). Opera is, however, best representative of the Marx Brothers’ wide array of talents as comedians, musicians and indeed even thespians and contains a few of the brothers’ most classic comedic routines. First we must trudge through the history of the brothers and their journey from stage to screen to understand how personally A Night of the Opera might have resonated with their own experiences.

Backstage Backstory

A Night at the Opera lovingly (and caustically) highlights the very real “drama” of two opera singers struggling to break into the business. The simple premise: a fast-talking manager (Groucho) aims to bring about success for his two clients while skewering those standing in their way. While the specific roles and impetus for drama always changes, the Marx Brothers’ goal remains the same — mocking and ridiculing the lazy, snobbish, hypocritical establishment.

This premise carries extra weight considering the Marx Brothers began as a family of stage performers, primarily musical stage performers – well versed in the travails of live theater. In 1915, their other other brother Gummo left join the fight in World War I claiming, “Anything is better than being an actor!” Though we never get to know Gummo as part of the cinematic Marx Brothers, the comment boasts a requisite amount of truth through overextended absurdity. Classic Gummo.

Let’s rewind the clock a few years further. In 1910, Groucho and Harpo made up one-third of “The Six Mascots” musical act alongside Gummo, uncle Albert Schönberg, mother Minnie and aunt Hannah. It wasn’t until a 1912 performance at the Nacogdoches, Texas Opera House, that comedy entered their routine and even then only accidentally. During the show, many members of the audience abandoned the theater to witness the real-life and presumably gripping drama unfolding outside the theater concerning a runaway mule. When the patrons returned, Groucho began lobbing abrasive witticisms at the crowd like “the Jack-ass is the flower is Tex-ass.” The abused masses laughed, and the family realized its potential as a comic troupe – though the focus for the time being would remain music. (Harpo claims in his autobiography that this incident took place in Ada, Oklahoma while a San Antonio newspaper claims Marshall, Texas. Set the scenario anywhere you please.)

By the early 1920’s, the Marx Brothers had shifted their act further toward comedy and became America’s favorite theatrical act. With an assist from renowned playwright George S. Kaufman (You Can’t Take It With You stands among many other entries on his mile-long resume), their musical comedies The Cocoanuts and Animal Crackers made them Broadway stars. It was this success that led Paramount to sign the brothers to a motion picture deal.

Their first two films, adaptations of The Cocoanuts (1929) and Animal Crackers (1930), both feel like filmed theater. The musical numbers were recorded on the soundstage with a live orchestra as they were performed. As new techniques for sound recording developed through the early 1930’s so too did the brothers’ proficiency with the language of cinema, climaxing with Duck Soup in 1933. Unfortunately the moviegoing public of 1933 did not agree with our current assessment of the film. Duck Soup, which contains 100% non-stop gags and bits and no musical numbers, flopped at the box office.

After the expiration of their Paramount picture deal, Irving Thalberg, over a game of bridge with Chico, first discussed bringing the four brothers to MGM to continue their film career. Thalberg insisted on a more scripted, less anarchic approach to filmmaking that would bring together all of the elements from their Vaudevillian performances and direct their biting candor at villains and deserving targets rather than any unfortunate that happened across their paths. The first collaboration between Thalberg and the Marx Brothers resulted in our Backstage topic at hand: A Night at the Opera.

The Sanity Clause

Groucho (Otis B. Driftwood) squints at the fine print on the contract, placing it at a precise distance in order to decipher the text and read it to Chico (Fiorello).

Driftwood: The party of the first part shall be known in this contract as ‘the party of the first part.’ How do you like that? That’s pretty neat eh?

Fiorello: No, that’s no good.”

Driftwood: What’s the matter with it?

Fiorello: I don’t know let’s hear it again.

“The Sanity Clause” scene skewers the incomprehensible contractual jargon perfectly. Groucho and Chico take turns removing nonsensical language until they’re left measuring the sizes of their papers to gauge the legitimacy of their agreement.

In addition to these bits of backstage logistics, A Night at the Opera contains scenes from the operas I Pagliacci and Il Trovatore plus another pair of large musical numbers. “Alone” features operatically trained co-stars Kitty Carlisle and Allan Jones crooning at each other during the departure of the steamship. Allen Jones again lends his voice to “Cosi Cosa” which is sung during the Italian buffet scene and accompanied by grand dance performance. The music in Opera comes more prominent than in past Marx movies, but this shift leads to some awkward transitions and curiously episodic creative choices as the tone shifts back and forth from Marx Brothers comedy to musical.

A Night at the Opera represents the Marx Brothers at their most diverse (at least during their on-screen careers), each performing the breadth of their immense talents. It is also the Marx Brothers’ shtick at its most structured and narratively driven. Thalberg believed that the negativity underlying their sharp-tongued wit made them unsympathetic and that as supporting players helping other characters achieve their goals, the more amenable Marx Brothers would regain their immense popularity. In a nutshell: twice the cash with half the laughs.

As a result, the Marxes intermittently cede the spotlight to their so-called supporting players. When Chico and Harpo replace the orchestra’s music for Il Trovatore with “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” this elaborate sabotage and subsequent chase allows Riccardo (Allan Jones) the chance to showcase his singing chops and upstage the pompous and preening established star Lassparri (Walter Woolf King). MGM and Thalberg had used the Marx Brothers to create a platform to showcase the studio’s matinee idol Allan Jones. Meanwhile, Groucho spends A Night at the Opera attempting to sell his star and unite young lovers rather than barreling ahead with more traditional, solipsistic motivations.

Despite the distractions of “narrative” and idol-pushing, A Night at the Opera boasts some of the Marx Brothers’ best routines. I’ve already noted “the Sanity Clause,” but I’d be remiss to overlook the “Stateroom scene.”A simple premise — packing as many Marx Brothers and ocean-liner service people into one tiny stateroom. Concentrated Marx. A gag pushed beyond the breaking point and anchored by Groucho’s matter-of-fact acceptance of the chaos swirling around him.

“And now, on with the opera. Let joy be unconfined. Let there be dancing in the streets, drinking in the saloons, and necking in the parlor.” -Groucho as Otis B. Driftwood

Using the film’s backstage narrative as a springboard, Opera may be the most authentic form of the Marx Brothers’ original stage act. Groucho himself considered A Night at the Opera and their next film, A Day at the Races, to be their best cinematic efforts.

Though the Marx Brothers’ A Night at the Opera is considered a classic (AFI ranked the film at #12 on its list of 100 greatest comedies), their transition to MGM marked the beginning of the end of the comic team. Thalberg’s theory worked, at least in the short term, resurrecting the Marx Brothers from critical purgatory and vaulting them back into the good graces of the audience.

Unfortunately for the Brothers (and Irving Thalberg), Thalberg died two years later of pneumonia at age 37 during production on A Day at the Races. The Marxes lost their advocate at MGM and decided to take their act elsewhere. Their next film, Room Service, produced by RKO marks a steep decline. Not only is it a lesser film, it wasn’t even conceived with the Marx Brothers in mind. The project had to be retro-fitted to suit their talents. A return to MGM produced three more lesser films before a pseudo-retirement from the big screen. Chico brought the team out of retirement for A Night in Casablanca and Love Happy in order to pay his massive gambling debts.

It’s easy to imagine that losing their creative control had some ultimate effect on the years that immediately followed Thalberg’s death. Perhaps the winds of change shifted the cinematic landscape and the Marx Brothers were just too tired by this point in their career to follow. The takeaway here is that the business of show is a brutal enterprise, stage, screen and beyond. Consider poor Gummo who would rather have gone to war than continue his acting career. Consider further that perhaps the greatest comedy ever made, Duck Soup, failed critically and commercially to the point that critics called for the end of their film careers. The Marx Brothers had to change the way they made films in order to justify their continued existence on the big screen. The squares and the boors might be the gatekeepers of the entertainment establishment, but at least we have Groucho, Harpo and Chico to take them all down a few pegs with witty barbs and embarrassing pratfalls.

God bless the Marx Brothers. (Even Zeppo, who I just now realized didn’t even get a mention in this blog post when even Gummo got two.)

Read the rest of the Blackstage Blogathon entries here: Day 1 Day 2 Day 3