#22. Suspiria (1977)

Nature of Shame:

First time on the big screen.

Hoop-tober Challenge Checklist:

Decade: 1970’s

I first saw Dario Argento’s Suspiria when I was 16. I backed into the Argento brand of Italian horror via the brief theatrical run of Michele Soavi’s Dellamorte Dellamore.

A one paragraph blurb the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette propelled me to see an Italian zombie movie playing at the Denis Theater. By this point, let’s say I’d… devoured… George Romero’s Dead trilogy so my interest in lumbering brain-hungry monsters had reached a crescendo.

In the part of my brain that might have otherwise been put to better use — by say, remembering a person’s name upon first introduction — I store information about the movies I watch. I can recall when and where I saw just about any movie, especially in a theater. Other cinephiles likely have similar powers, but muggles like my wife find this specific skill rather superfluous.

Built in the 1920’s and formerly a one-screen movie house, the Denis had divided its one large theater into four smaller ones. The upstairs house created using the balcony seats, where I saw Dellamorte Dellamore, provided the unique perspective of looking down onto the film. I only saw one other movie on that particular screen — David Cronenberg’s Crash (1996).

This viewing of Dellamorte Dellamore, or Cemetery Man as it was called during its US release, remains one of my most memorable theatrical experiences. Both the movie and the unusual experience contributed to this visceral memory. I detail this experience because as movie fans we always have those benchmark moments when our cinematic frame of reference suddenly and often violently gets thrown into flux. If movies like Michele Soavi’s poetic metaphysical Euro-trash zombie comedy existed what else might I find if I dig deeper into Italian horror?

In that Pittsburgh Post-Gazette review of Dellamorte Dellamore, the author called Michele Soavi a “Dario Argento disciple.” I went to Blockbuster Video the next day and rented the only Argento film they carried — Suspiria. I fell in love. I began ordering bootleg Argentos unavailable in the United States. In college I served up Opera (1987) to my unsuspecting friends one Halloween. 22 years later, I finally had the opportunity to see Argento’s masterpiece on the big screen.

The Story

American ballet student Suzy Bannon arrives in Germany to join a prestigious dance academy. Upon arriving late one stormy night, she’s denied entry, and a frantic girl exits the building babbling incoherencies. In the first of many troubling events, the girl is found murdered, stabbed and hung from the ceiling of a friend’s apartment building.

The next day, Suzy returns to the Academy and meets the staff and students. During her first session, Suzy faints and is prescribed a specific diet to “build up her blood.” Forced to reside on campus due to her illness, Suzy befriends a girl named Sara, who shares with her information about Pat, the girl who evacuated the building that first night, and the suspicions Pat held about the teachers and administrators at the school.

Maggots rain from the ceiling. Sara disappears. The blind piano player that scored the students’ practice is killed by his seeing-eye dog. Suzy starts to put the pieces together and unravels a centuries old mystery.

Dario Argento champions style over substance. Argento critics recite the phrase ad infinitum. But what if style is the substance? Filmmakers generally — as visual storytellers — must use an aesthetic to serve their narrative. But is it actually a negative when a filmmaker wraps narrative over an aesthetic to the extent that the story itself seems like the accessory?

The criticism arises most frequently when flaws can be found in other aspects of the production. With regard to Suspiria, I’m not blind to the inadequacies of the screenplay or the narrative simplicity; however, Suspiria‘s flaws do not detract from the tension as Suzy delves deeper into the bowels of the estate and they certainly do not tarnish Argento’s phantasmagoria of color and haunting soundscapes.

The weary “style over substance” criticism has been applied to films as long as projector gears have been turning. Critics hid this negativity behind layers of formal, ornamented prose, but their intent remained clear. Upon its release, German critic Herbert Jhering said of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920): “If actors are acting without energy and are playing within landscapes and rooms which are formally ‘excessive’, the continuity of the principle is missing.” Jhering could have said the same about Suspiria 57 years later. Filmmakers as widely disparate as Sergei Eistenstein and Jean Cocteau echoed similar sentiments about Wiene’s masterpiece of surrealist cinema.

The most troublesome aspect of the modern use of “style over substance” isn’t its omnipresence. It’s a phrase that professes sincere criticism but offers none. I return to the thought that style in a visual medium is nothing short of substance. However, that a film values aesthetics first neither betrays nor necessarily elevates other aspects of filmmaking. A beautiful film may be resplendent, but it might also be vapid. The question must be: Does style contribute to the success of the filmmaker’s vision?

Nicolas Wending Refn dwells in that perverse balance of style and substance. Consider the differences between Drive (2011) and his latest Neon Demon (2016). Where Refn uses substance to propel and embellish a standard narrative in the former, a similar overall aesthetic fails to support the labored metaphors of the latter. Speaking of “labored,” this has been a convoluted way to state the obvious fact that the value of a film is a subjective verdict weighed against dozens of different aspects of filmmaking working together to unite a collection of signs and signifiers.

With regard to the production of Suspiria, Dario Argento clearly set forth to produce a visual and aural spectacle that titillated the senses and immersed the viewer into an otherworldly atmosphere. He bathes the viewer in an unnatural palette of gaudy blues, purples and reds. Blood spurts orange. Any individual frame could be used in a master class on composition and lighting, and these stylistic choices all contribute to the instability and visceral unease that the audience shares with Suzy Bannon.

Final Suspiria Thoughts:

Before heading off to see Suspiria on the big screen, I tossed in my old Anchor Bay DVD. I wanted to take one final look at the traditional home video color palette for this film before basking in the restoration work done by Synapse. Even though I’d only seen glimpses of the new images, it felt bleak.

I’m happy to report that everything I loved about Suspiria has been magnified. The big screen immersion just cannot be replicated at home — and maybe not even by the pending Blu-ray release. The colors envelop you — Argento’s grip is firmer, the tension more present. You’re properly captive. If you’ve never seen Suspiria on the big screen — or better yet, if you’ve never seen Suspiria at all — I cannot properly convey without a string of expletives how strongly I feel that you must see this film theatrically to properly judge Argento’s “style over substance.”

And do me a favor, if you still default to using “style over substance” as a criticism, follow that up by discussing how that style fails to support the filmmaker’s intent. Only then can we have a proper discussion about the value of Suspiria.

30Hz Movie Rating:

Availability:

Pre-order the Synapse 3D Limited Edition Suspiria Steelbook from Diabolik DVD. This will, without a doubt, be the definitive version of the film on home video.

2017 @CinemaShame / Hooptober Shame Statement

31+ Days of Horror. 33 Horror Movies. 33 Reviews.

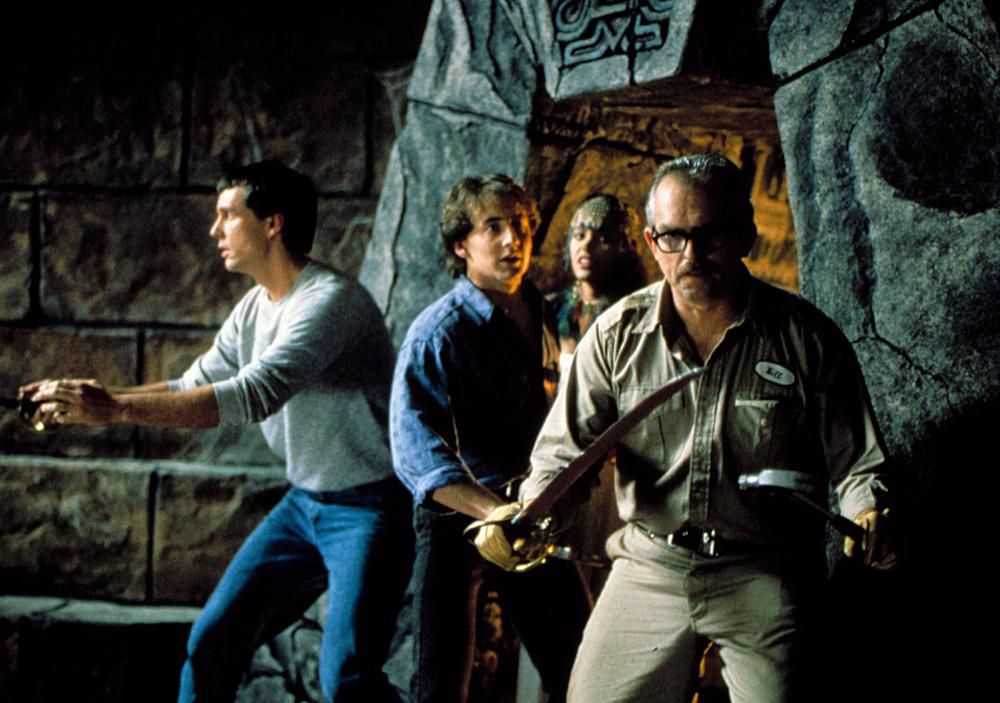

#1. Caltiki The Immortal Monster (1959) / #2. The Devil Doll (1936) / #3. The Velvet Vampire (1971) / #4. Mill of the Stone Women (1960) / #5. The Initiation (1984) / #6. Poltergeist (1982) / #7. Night of the Lepus (1972) / #8. The Black Cat (1934) / #9. The Raven (1935) / #10. Friday the 13th (1980) / #11. Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981) / #12. Body Snatcher (1945) / #13. Dismembered (1962) / #14. From Hell It Came (1957) / #15. Symptoms (1974) / #16. Eating Raoul (1982) / #17. Spellcaster (1988) / #18. The Old Dark House (1932) / #19. House (1985) / #20. House II: The Second Story / #21. Christine (1983) / #22. Suspiria (1977) / #23. The Invisible Man (1933) / #24. Spider aka Zirneklis (1991) / #25. The Wife Killer (1976) / #26. Cannibal! The Musical (1993) / #27. The Wicker Man (1973) / #28. Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986) / #29. Night Creatures (1962) / #30. Nosferatu (1922) / #31. Wes Craven’s New Nightmare / #32. Day of the Dead (1985) / #33. Psycho II (1983) / #34. The Green Butchers (2003)

Hoop-tober Challenge Checklist:

Hoop-tober Challenge Checklist: