Universal Horrors: The Studio’s Classic Films 1931-1946

by Tom Weaver, Michael Brunas and John Brunas

McFarland & Company; 2nd edition (February 15, 2007)

608 pages

ISBN: 0786429747

When I dared to undertake the reviewing of six books about classic cinema in addition to my regularly scheduled summer fiction regimen, I should have had the foresight to choose something other than a textbook-sized compendium on every horror and horror-related film released by Universal during their first and second horror cycles.

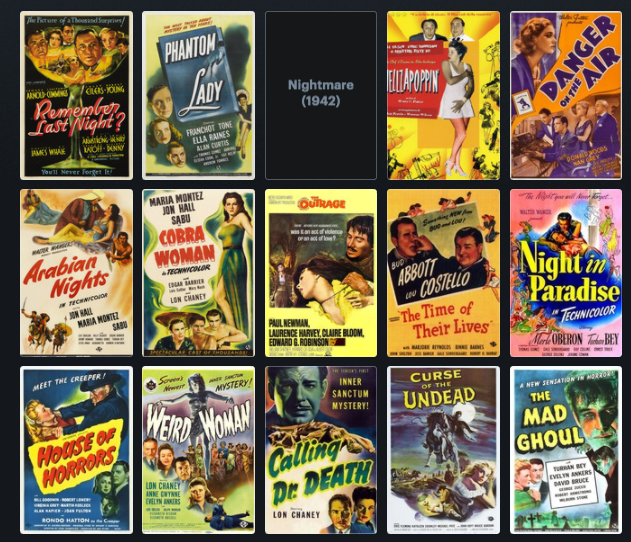

I once claimed proficiency in these types of films. Now, I find that notion “quaint” and perhaps “simple-minded.” I’ve only scratched the surface. Sure, there’s the roll call of A-list monster titles that we all know and love. Dracula. The Wolf Man. Frankenstein. And my own personal favorite, The Mummy. But then there’s all the rest. I suppose I originally engaged with this book because I wanted to know about those gems that slipped through the cultural cracks.

Be careful for what you wish. (Using that, the grammatically preferable form of that statement, makes it sound positively Lugosian. Say it out loud. Claw-like hand gestures optional.)

Universal Horrors excels because the authors not only document these forgotten films (also orienting them in time and space with relation to the more popular films that overshadowed their existence), but they dare to offer a definitive opinion about every single film. Since many of these gems require a bit of hunting to track down, the opinions contained within certainly help focus my attentions on worthy searches. Only once do I recall the authors throwing up their hands in futility because they couldn’t track down a copy of a film.

Universal Horrors covers 86 films in great detail, diving into great detail about the behind-the-scenes production, the temperaments of the actors involved, and the contemporary reception upon release. Stories told to the authors by surviving cast and crew pull back the curtain on the Universal production demands of the era. Though I knew quite a bit about the rigorous studio demands on their creatives, I repeatedly found myself surprised by the regard (or lack thereof) with which Universal treated these cogs in the machine.

It’s particularly interesting to chart the course of the studio’s major players — Bela Lugosi, Boris Karloff and Lon Chaney, Jr. — as their careers carried on beyond the iconic roles of Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster and the Wolf Man. The authors also, in no less detail, devote substantial sections of the book to the lesser stars of the era such as Gloria Stuart, Evelyn Ankers, Dwight Frye and Maria Ouspenskaya, just to name a handful of the players brought to life again on these pages. The tragic figures on the screen often mirrored the real-life tragedies of the people responsible for these beloved Universal horror films.

Universal Horrors becomes a grind — as would any book of this nature — because it labors over plot synopsis for each of the entries. For certain films I welcomed the refresher course, but by and large, these retellings interrupt the torrent of more interesting bits of cultural context and production details. Thankfully, the authors quarantine the synopses, never burying interesting nuggets among the rote regurgitation, making them easy skips. You’ll welcome the opportunity to move along on page 400 or so during another middling entry in the Inner Sanctum series.

It’s possible that Universal Horrors would appeal mostly to die hard fans of the genre, but due to the depth that the authors go to document the era, the book should appeal to all fans of classic cinema. Hearing the words of Universal’s contract players and indentured filmmakers of the era sheds light on a time and place and a production style (movies written and filmed in under twelve days!) that seems alien by today’s standards. It’ll make you nostalgic for a moviemaking business that wasn’t so damn serious, when horror movie monsters were an ironic escape from the horrors of a decaying world.