Cinema Shame: Once Upon a Time in the West

Scratching an entry off my 2018 Shame Statement that also qualifies for the April Shame Prompt.

Seeing as how the April prompt concerned movies screened at this year’s Turner Classic Movies Film Festival in Hollywood April 26th-29th, I had a distinct advantage of attending the festival. So any movie I hadn’t already seen fulfilled the requirement. This year I first-watched 10 movies at TCMFF, but it seems only logical that I grapple (finally) with Once Upon a Time in the West — a movie I’ve owned on both DVD and Blu-ray for at least 10 years, but never watched.

There’s nothing easy about committing to a 175-minute movie. I even considered missing out on the chance to see Once Upon a Time in the West at the TCL Chinese Theatre. Which is pure insanity. I blame “festival brain” which clouds rational thought. I should love everything about this movie. I just needed to place my posterior in the seat. So I did, at 9:15 am on Sunday with a big bag of popcorn and my Ray-Bans obscuring the sleep deprivation in my eyes.

From the opening minutes on the IMAX screen at the TCL Chinese Theatre, the sweeping vistas and vintage Leone closeups made me feel like I was experiencing the most cinematic thing ever committed to film.

The film’s opening is a nearly wordless 15-minute sequence in which three gunmen (Jack Elam, Woody Strode and Al Mulock) do nothing more than wait for the arrival of another character on a train platform in a remote frontier station. Before you express your disinterest, would you believe me if I told you it was my favorite 15 minutes of movie I’ve seen in recent memory?

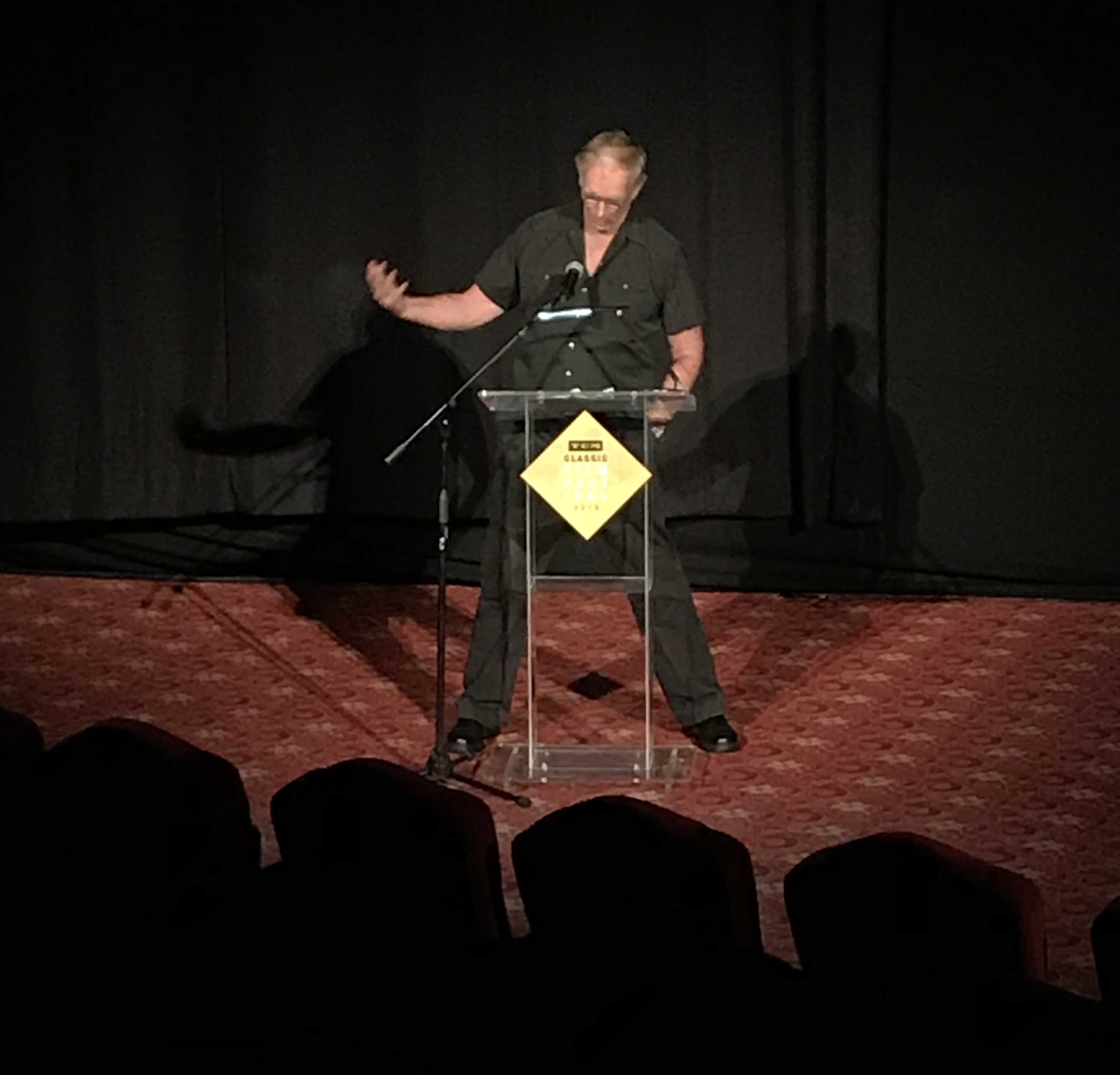

It is of course, for you Western fans, a reference to the opening of High Noon — where three malcontents similarly await a train’s arrival. John Sayles, in his introduction to our screening of Once Upon a Time in the West, described how Sergio Leone, Dario Argento an Bernardo Bertolucci cobbled the narrative out of bits and pieces of their favorite classic Westerns. In doing so, these three Italian auteurs may have made the final stand in the classic Western era. What more needed to be said after Once Upon a Time in the West?

The most remarkable aspect? In creating this tapestry, they’ve so masterfully woven the story and influences together that the viewer stops looking for the connective tissue and just basks in atmosphere and spectacle.

Leone reportedly wanted Once Upon a Time in the West to be a metatextual conclusion to the Dollars Trilogy. He’d wanted to cast Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef and Eli Wallach as the gunmen in this opening sequence. When Eastwood declined, Leone scrapped the notion and cast the veteran Western actors Elam, Strode and Mulock instead. Losing perhaps his connection to Dollars, but extending his reach further into the history of the genre, recalling films beyond his own.

Leone increases the tension through the use of sound (and the absence of) and anticipation. A squeaky door. A windmill in need of some oil. Ambient cooing of a bird in cage. Footsteps. Spurs on a wooden floor. The gunmen idle, awaiting that train that will carry their unknown target. Elam tracks a fly buzzing over his face. Strode stands beneath a drip and collects water in his hat. Mulock cracks his knuckles. Each action contributes to Leone’s isolated soundscape, meticulously crafted through post-production foley recording.

The audience brings their own expectations into the scene. The audience assumes that the men anticipate the arrival of Charles Bronson’s character, and the longer we wait the greater the anticipated payoff.

The train arrives just under 10 minutes into the film. The door to a freight car opens, causing Elam to flinch. An attendant tosses out a single box and then the train begins to depart.

The gunmen gather on the craggy platform, facing away from the train. Finally we hear a new sound — the first hints of a Morricone score — a harmonica. The ne’er-do-wells pause. Elam’s expressive eyes rise in acknowledgment of the music.

A distant figure appears on the far side of the tracks as the train vacates the station. Perspective dwarfs the shadowy figure in the background, but the specter of Bronson — the on-screen persona and the legend built by 12 minutes of anticipation — looms large.

I won’t spoil it for you when I say that the hero survives the first scene of a 3-hour film. Bronson dispatches the gunmen — in a classic Leone showdown — and then the movie begins.

If it sounds like I’m gushing, it’s because I’m absolutely gushing. I could go on like this describing two or three more sequences from this film that similarly stir my cockles.

Once Upon a Time in the West depicts three conflicts that take place in and around the fictional town of Flagstone. There’s a financial tycoon Morton hires a cold-blooded blue-eyed assassin Frank (Henry Fonda) to eliminate the McBain family standing in the way of a potentially valuable piece of property — a narrative that’s become complicated by the arrival of a New Orleans prostitute (Claudia Cardinale) who claims to be McBain’s wife. Frank frames local bandit Cheyenne (Jason Robards) for the McBain family massacre.

Meanwhile, a mysterious outsider, the Bronson character (later dubbed Harmonica by Cheyenne) tracks Frank — with eyes on an uncertain vendetta to be paid. Harmonica and Cheyenne become unusual allies against Morton and perhaps reluctant defenders of McBain’s widow.

John Ford ectoplasm oozes all over this film — but we’re seeing John Ford through a disillusioned gaze. A look back at the old West filled with decay and lacking the proper delineation between hero and villain. There’s plenty of villain, but Leone dispatches the notion of a pure hero. Even the heroes in Once Upon a Time in the West are part scoundrel. They’ve taken on the role of hero because their interests align with the moral right as perceived by the audience.

Despite the 176-minute runtime, Once Upon a Time in the West never feels aimless. Leone allows the audience to dwell on the hardened faces of his characters just as he embraces the beauty and desolation of the natural landscape. Every frame feels pointed towards their inevitable fate — a fate that echoes that of the American old west and the Western genre. Assimilation or elimination by the progress brought about by industrialization and the spread of civilization.

In cinematic terms, the audience’s interest in the genre declined with the rise of the blockbuster. Galaxies far, far away opened up with the help of increasingly elaborate special effects.

The Western genre met a kind of end as the 1960’s came to a close. Once Upon a Time in the West represented a master’s final volley, the last word on the matter. In many ways the genre represented a uniquely American romanticism about the wide open spaces, a limitless potential — but also the dark underbelly that went along with it. A blank canvas for starkly moral fables about good and evil. After Once Upon a Time in the West, westerns began to more fully embrace the “anti-Western” trend that had been growing since the early 1950’s.

After the success of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), the 1970’s saw a wave of Western Revisionism and uninhibited creative freedoms in films like Little Big Man, El Topo, McCabe & Mrs. Miller before the genre rode off into the sunset almost entirely at the start of the 80’s.

If this is the end of the Western genre proper, I can’t imagine a more fitting conclusion. After Once Upon a Time in the West there really wasn’t much more to say. Or at the very least it feels that way.

2018 Shame Statement Update:

(Bold/linked denotes watched)

Five Easy Pieces

Lifeboat

Stop Making Sense

The Black Pirate

Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer

Paris, Texas

Wuthering Heights

Paper Moon

Sunrise

The Conversation

Victor/Victoria

Once Upon a Time in the West

Ikiru

Help!

Cinema Shame Monthly Prompts:

January Prompt: Shame Statement

February Prompt: An American In Paris

March Prompt: The Crimson Pirate

April Prompt: Once Upon a Time in the West