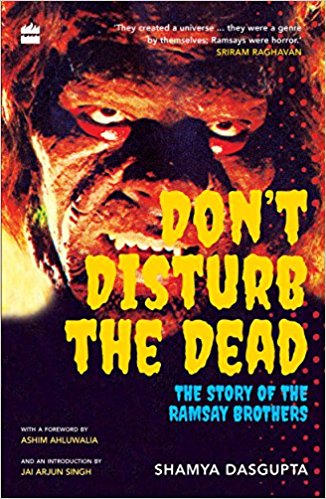

Don’t Disturb the Dead: The Story of the Ramsay Brothers

by Shamya Dasgupta

Harper Collins India (June 5, 2007)

238 pages

ISBN: 9352644301

Unwittingly my Classic Film Summer Reading Challenge jumped from the pioneers of American horror films at Universal Studios to the pioneers of horror on the subcontinent — the Ramsay brothers.

For those that haven’t been exposed to the Ramsay oeuvre, I’ll give you quick rundown of the fundamentals. Low-budget amalgamations of violence, gore, ancient curses, atmosphere, monsters, voodoo, skin and (always obscured) sexuality, and traditional Bollywood musical numbers. Until one has seen a Ramsay film, a Western viewer likely will not understand how all these pieces fit together. Even though I’d been aware of the Ramsays as filmmakers, I couldn’t wrap my head around the notion of a Bollywood horror film. And then I watched Veerana for my Halloween Horror Challenge last October.

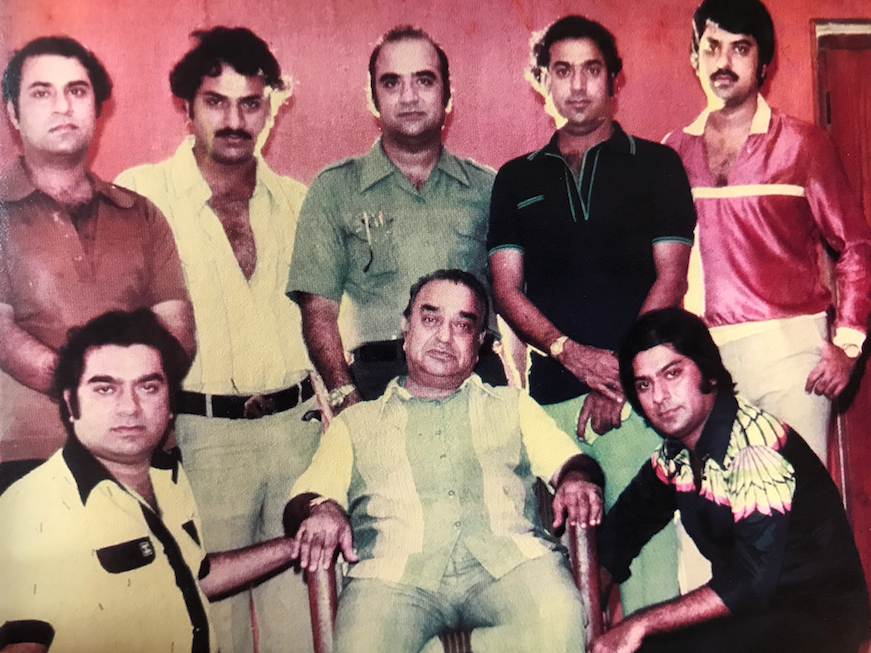

The Ramsays were a family of filmmakers that discovered an untapped niche in the Indian film industry. Until the early 1970’s when the Ramsay’s conquered the market, no one in India made horror films. Despite their financial success, they met both cultural and market-driven barriers to widespread acceptance. Conservative viewers condemned their risqué output, and operating as independents outside the Bollywood system caused friction within the traditional chain of release. As a result, the Ramsays peddled their spook films to areas outside major metropolitan areas. Over the years their films became events, celebrated entertainment for the masses, but they also never gained the respect bestowed upon successful filmmakers.

Before viewing Veerana, I knew the Ramsays only by reputation. India’s version of Hammer Horror. In as much as that rings true (they Ramsays modeled themselves after Hammer studios) it also sells their enterprise short. Using Hammer as inspiration they created culturally specific horror films that defined a generation.

Don’t Disturb the Dead breathes life into the Ramsay’s global reputation by focusing on the way the filmmaking collective assembled an internal team of directors, editors, cinematographers, costume designers, set designers and shot full-length feature films on shoestring budgets and cultural limitations.

As my exposure to Bollywood is limited, the names and places that Dasgupta spouts as reference points for the Indian film industry models of success and failure wash over me. At first I spent time looking up each name, but this grew tiresome and I soon left explanation to authorial context. As a comprehensive history, Dasgupta relies on familial anecdotes and therefore fails to convey a concrete sense of history. Many stories are undermined by the hazy or conflicting recollections among the surviving Ramsays. In many ways this seems fitting coming from an industry that even into the 1980’s believed that cinema was merely a transient form of entertainment. The lack of preservation has left us only with storytellers.

The English-as-Second-Language translation of Don’t Disturb the Dead could be viewed as a detriment as well. The narrative descriptions sometimes feel clipped from amateurish imdb.com synopses. Take for example the following description of the film Darwaza (1978):

“Let’s go over the story, though it’s more more fun – obviously – watching it; if nothing else, for the atmospherics of fear, the sheer spookiness of it, the effect of the hand-held camera sneaking up on you, which is something Gangu uses is many of the films very smartly. Ye, the screaming Ramsay leading ladies are all there somewhere, and so are some random bits, but it’s a taut screenplay, all of it leading somewhere, and, before the end, there are a number of questions that remain, which keep you hooked. And spooked.”

Long segments of interview with some of the Ramsay brothers appear unedited and these, translated into English, also offer some simple charms where translation has made an earnest attempt to turn Indian idioms into proper English. I made a point to mark a quote from Arjun Ramsay (editor): “You can’t only add chili in your food – thoda khatta, thoda meetha (a little salt, a little sugar) … and we did what we did and the aim was that the audience liked it.”

The structure of the book allows for an occasionally maddening centripetal nature. Don’t Disturb the Dead highlights the different parts of the production team, but as Dasgupta begins each segment he takes us back through the Ramsay filmography as it serves the topic. Rather than going film to film and organizing his thoughts chronologically, he continually circles back. While this allows each of the brothers to get a moment in his spotlight throughout the production chain, it also creates a Back to the Future-esque branching timeline for someone unfamiliar with the films and Bollywood players that float through the Ramsay’s story. From his perspective, this serves a specific end: the movies themselves stand as a testament to the family that made them and the stories they told and shared. Readers will note a specific, culturally-ascribed attitude difference toward the actresses in their films and the women in their family, but we must view these through an appropriate lens.

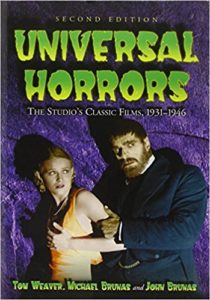

While not an especially exhaustive discussion of the films themselves (I did just read an encyclopedic textbook about every Univeral horror film), Don’t Disturb the Dead paints a specific picture of familial devotion and the closed-circuit nature of the Indian film industry. Little scholarship has been devoted to the Ramsays, and their films remain underseen curiosities in the West. I would be shocked if someone read the introduction to this book and wasn’t at least curious enough to check out a Ramsay movie… or at least a clip.

If Dasgupta manages to expand the Ramsay’s audience and finds a few more fans in the West, he’s done his job. Even though the movies will look rather cheap and more than a little silly to our eyes, there’s talent and devotion to the craft behind these escapades that welcomes sincere and ironic enjoyment in equal measure.

Luckily, the films are now available on YouTube for our enjoyment. Here’s the film that jumpstarted my curiosity in the Ramsays.