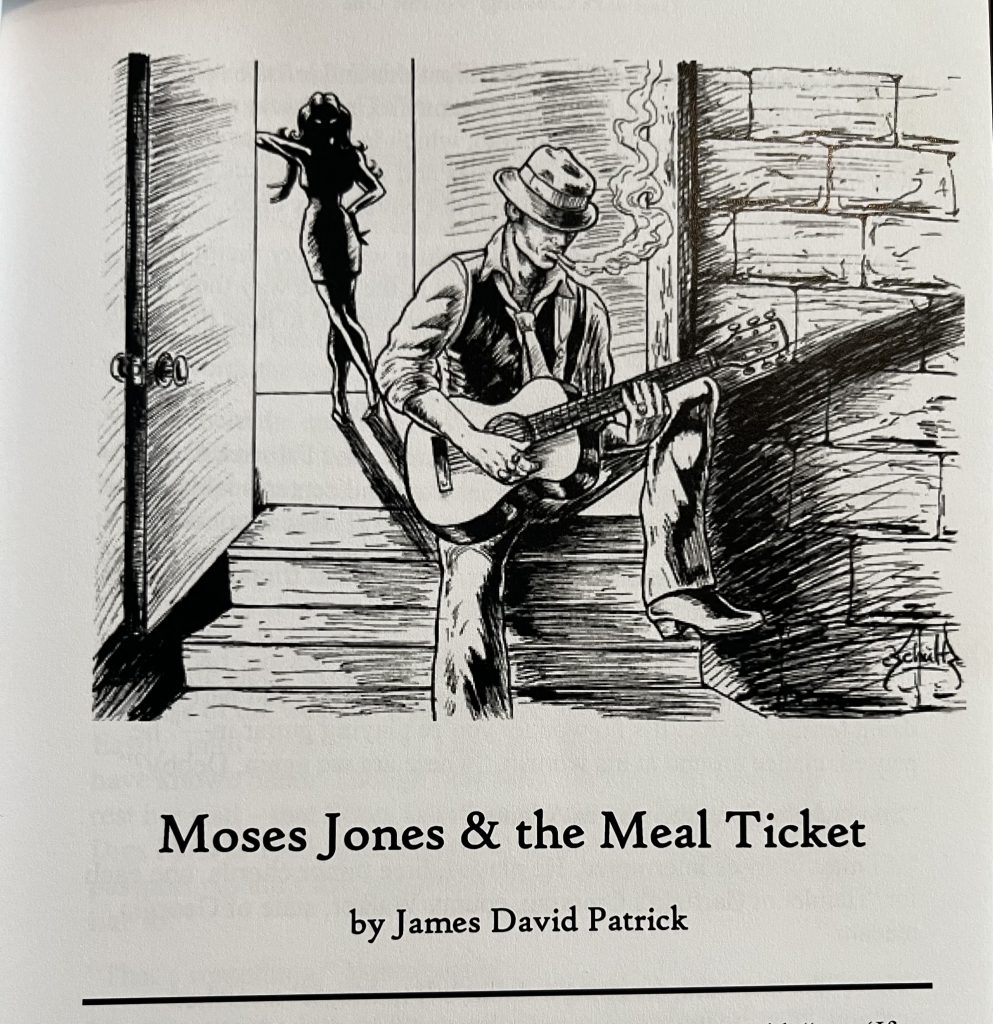

by James David Patrick

(originally published on Garfield’s Crossing, available in the Garfield’s Crossing Vol. 1 Anthology)

“The best thing anyone ever said to me,” Moses Jones said, “was ‘If you don’t get outta my way, your lips’ll be replaced by the flappin’ sole of my left boot.’ Now this piece of advice left a proper impression and one very important lesson. First, I didn’t know if that old snaggletoothed reprobate was left-footed or if only his left shoe was in need of repair. And second, when someone is bound and determined to remove you from your place, you best stand aside with a wave and a smile. Otherwise, feel free to stay put.”

The seated crowd of early-evening drinkers, teetotalers and idle sippers paid the bluesman little mind atop his raised platform. They carried on with their conversations, swilling their libations and left the rest to Moses Jones, musician in-residence at Jenny’s Crabshack, a seafood dive that only occasionally served crab, which in itself, Moses noted, was something deeply rooted in the the blues and if a crabshack could write songs, it would write songs about not having any crab.

The patrons at Jenny’s wanted to let the blues wash over them; they wanted to remember that the blues existed in the same way they kept their grandmother’s Lou Rawls records; they wanted to hear the blues and abandon it at the door on the way out.

One man, however unfortunate, had been listening.

“Moses,” the man said, “stick to playing guitar and I’ll stick to drinkin’ this beer, alright?” The man sat front and center – table two – with a woman who whisper-yelled, “Shut up, Bill. Just for once.”

Moses never failed to indulge a listener. “Why’s that friend? Are you not partial to my interludes?”

“Well, Moses Jones, you see that first part of your ‘lesson’ back there was nothing more than an idle ponderance and the second part is just damn terrible advice. It’s no wonder you’re playing guitar in—“ he paused, glance around at his woman, “where are we again, Debby?”

“Somewhere along the way to Atlanta.”

“If I may,” Moses interrupted. He played three minor chords, one each for “Hamlet of Garfield Crossing, county Walker, state of Georgia, madam.”

“Here,” the man said, dropping a dollar bill in Moses’ tarnished spittoon. “For the information and a little of the guitar plucking. But not for any of those life lessons.”

Moses had inherited the spittoon from his grandfather who’d allegedly run away into the wilderness never to return. Not too far away from here. Nan had been prone to hyperbole and warm whiskey so the facts surrounding Pap’s departure remained hazy. Moses kept the spittoon as a reminder not to run away into the wilderness with those wayward and desperate Appalachia bears and man-eating kudzu vines.

“Going to Atlanta, folks? Nice town. You from there?”

“Visiting relatives,” Debby said. She was kind eyed. Moses wondered how she wound up on Bill’s arm.

Atlanta got Moses to thinking again. And when he started thinking, he started talking. “My nan lived in Atlanta for spell,” he said. “Cleaning houses. Here and there.”

Bill tapped a cigarette pack in his palm. “I’ll be back,” he announced and then stepped outside through the back door, not at all interested in Moses Jones’ pending story about his nan, which was a shame because it was worth the wait.

A brick held the emergency door open for anyone that needed a smoke. Jenny had mounted a sign on the door warning people about the alarm but no alarm was ever installed. But the door did lock from the inside and nobody had a key, which was the reason for the brick during operating hours.

“Funny story about my nan,” Moses continued. “She once told me that she’d had ‘relations’ with Dizzy Gillespie in the bathroom of a no name café along the Champs Elysées. And here’s the funny part. Because of the way she’d pronounced it, I’d called it the ‘Champs Easily’ until I was 17. Now I ain’t never been to France, but I should have known better. Though I did learn after my nan’s passing – God rest her soul – that Dizzy Gillespie had been in Paris recording Dizzy Digs Paris in 1953, which matched up with the stamp my old nan’s passport. So ain’t that something? One of these days I should visit. I’d like to.”

“That’s something,” Debby added.

Moses noted the lack of irony; sincerity such as Debby’s had become a commodity.

“Want to see something else?” Moses asked. He thought he had a good eye for people and that this Debby was on the level.

Moses waited a moment to smell the sweet tobacco and then casually, carefully, stood and walked over to the door. While tossing a “Hey,” at Cheri, the waitress with the lazy left eye, Moses nudged the brick back inside with his heel. Moses’ hip wailed where he once took a crowbar over twelve dollars, but every bluesman needs his fuel. “Brick slipped,” he said with a wink. “Don’t mention my assistance.”

Cheri sighed and carried on. She was probably going to tell Jenny about the brick.

The door shut hard. The evening draft and the sweet tobacco disappeared. Bill rapped against the metal door, but not even Debby jumped to let him back in. Didn’t much look like a man anyone with Debby’s kind eyes would miss. She smiled at Moses Jones. He smiled back.

“I should probably go get him,”

“Nice meeting you, Debby. Or maybe you prefer Deborah?”

Debby slung the strap of her purse over her head. “I’ve never actually thought about it. I do like the way ‘Deborah’ sounds, but only when you say it, bluesman.” Then she stepped out through the back door, too, where she was met with the voice of an annoyed Bill and the purposeful waving of a detached hand holding a cigarette. At least from Moses’ perspective. Deborah took one final glance over her shoulder. She eased the heavy door closed, and then she was gone.

Moses returned to his chair, picked up his guitar and rested his fingers on the strings, wondering again if that cat gut thing was always an old wives’ tale or if strings were sometimes still made of cat gut. He could never remember how that went down, but he swore his A-string shrieked like a cat when he hit it just so. Moses played a riff. An Albert King go-to he had rattling around in his head. Ring finger. Full-step end. Root repeat. Index for the bend and wobble. No one had taught him to play the guitar; he’d listened to his ma’s records and just picked it up. His dad told him to learn a trade, use his hands. He just wasn’t all that specific. When Moses played, his dad just said, “I was thinking more of carpentry or plumbing.” His ma nodded. He wasn’t discouraged so much as ignored and that was all right.

A body idled nearby. Standing by the doorway. How long it’d been there, Moses didn’t know, but it was there and so he looked up to take stock of it. First he saw a guitar case. Then he saw a teenager, a toddler really, nothing more than an assemblage of scrawny and awkward pieced together by hormones. He wore a shirt with a little stitched gator, untucked, navy and some cargo shorts with a hole in one of the side pockets. Burnt through maybe, since it looked cauterized and not too scraggly.

“Now what do you mean by all this deafening silence?” Moses asked.

“I don’t mean anything by it, sir. I just want to say that I’ve been doing a lot of traveling around this area, and I haven’t ever seen anyone play quite like you.” He paused. “That was King, right? Albert King? Not B.B. of course.”

The youth at least had some real learning behind his clueless exterior. It didn’t make Moses more inclined to talk about other things. Moses just nodded because that was usually more than enough for whatever the occasion.

Not nearly pacified, the boy parked himself on the riser and extracted a guitar from the case. From his chair atop the riser, Moses had a bird’s eye on the top of this boy’s head. Moses leaned a little further to get an eyeball on the boy’s ability.

“Would you play that song again?” the boy asked.

Moses obliged. The kid joined in eight beats later, echoing his riff. Moses moved on to a thing he picked up from Stagger in Texarkana. Or maybe it had just been that blind man in Little Rock. Either way. The kid shifted to get a better look at Moses’ fingering and then followed him through. Lagging a bit behind, almost harmonizing.

“That sounds like something from Johnny Moore. A sliding IV6-IV9 chord pattern. Simple, but timeless.” A small crowd had gathered to gawk at the teenager playing a guitar. Turning the riff from Stagger (or the blind man) into something else, taking it down, slowing the pace before bringing it back up. Money appeared in the spittoon; Moses was under no obligation to refuse. He nodded in thanks, but he figured it was back pay anyway for the tips they didn’t give him earlier. The kid slapped his palm across the six strings and silenced his instrument.

“Don’t let me stop you, son. Moses Jones ain’t got nowhere to be except maybe on break in five-ten minutes.” Moses had counted seven dollars come in since the boy sat down. There weren’t even that many people in this speakeasy, though Moses was never very good with numbers. Probably why he became a bluesman instead of a carpenter or a bank clerk.

“You are Moses Jones. I read about you in that Rolling Stone article on Stagger Lee Perry.”

“If you’re my ex-wife’s lawyer or that pimp from Scranton that mistook me for dine-and-dash John Doe, the name’s Frederick Alabaster.”

“It was more of a blurb really, no more than a sentence, but you were definitely mentioned.”

“Much obliged.”

The boy extended his hand. When Moses reciprocated he thought he’d probably about then stop thinking of him as a boy. His fingers dug into Moses’ hand like a waitress stiffed a tip. “William Lancaster, the third.”

“No, no, no, no that won’t due, not for a bluesman.” Moses paused, his hands palm down on his knees. “Truth be told, I don’t know what we’re talking about anymore. Talkin’ bout names, places…” He stared at the floor. “Oh, yes. You asked why a guy like me is holed up in Jenny’s Crab Shack that don’t serve no crabs. Well, I’ve got at least a dozen reasons. It’s a helluva story how I ended up here, but it’s a helluva story how a man’s life takes him anywhere. Take the Old Testament for example.”

“Is that Jenny?” the boy asked, tossing his head toward the arched doorway between the bar and the sincerely decorated blues room. Quite literally a blue-painted room in which Moses played the blues. Jenny stood in the doorway, polishing a glass.

“That fork-tongued she-devil’s always watching,” Moses said. He smiled broadly. “How you doin’, Jenny?” but Jenny just rolled her eyes.

Moses promptly picked up his guitar and monkeyed with something that sounded like “The Devil Went Down to Georgia,” but that didn’t go anywhere so Moses relaxed his fingers, laid his guitar down in its plush velvet bed, but didn’t shut the case.

“I heard we found somebody that can actually play a guitar,” Jenny said as she approached the riser. She glanced at the boy. “You doin’ alright, hun?”

The boy nodded. “Just fine, ma’am.”

“We’re fine, Miss Lady.” Moses added. “I’m going to take a few minutes to soak, if that’s alright with you.”

Jenny smiled at the boy and returned to the bar.

Moses grabbed the boy’s shoulders and spun him back around. “Bluesman lesson number one. Don’t you dare look the devil in the eye. But don’t you let her know you’re avoiding her neither. Pay attention. This is important because you’re going to meet the devil in a dozen different forms and you got to recognize that devil wherever she or he might be. You say, ‘I’m good, devil woman and don’t you think you can buy my pleasure and patience with your manners and perfume that smells of hollyhocks.’ You never give the devil none of yourself. All that belongs to you is yours.”

“She seemed nice.”

“That’s what the devil always wants you to think.”

“What?”

“No more questions about women, son. It’s too early for that and I’m hungry. Let’s continue this conversation over a bite.”

Moses beckoned William to follow him and led the boy out the emergency exit. William hesitated at the “Alarm Will Sound” sign but Moses had already pushed open the door.

The street lights hummed and flickered, pale and sick, like the smell of the dumpster contributed to their well-being. The air stank of Georgia humidity and festering July garbage.

Moses knocked on the neighbor door, waited, and then knocked again. After a moment, the door opened outward. A man of some anonymous Asian descent stood silent and waiting for an introduction. Moses obliged. “Kid, this is the Shanghai-Man. Shanghai-Man, this is a kid. I call him Shanghai-Man because he doesn’t like the term ‘Chinaman,’ even though he was true and through born in Shanghai.”

“It’s pretty damn racist out of context,” the Shanghai-Man said, devoid of any accent. “If I’m being honest.”

“It’s true, though.”

Shanghai-Man shrugged. “You come for your soup, Mose? Or just stand next to dumpster and discuss the institutionalized racism inherent to labels based on place of birth?”

“Two soups. Save the discussion for the off-duty bái jiû.”

Shanghai-Man shut the door and disappeared inside.

“What’s bái jiû?”

“Chinese rocket fuel. Now, your momma know where you at?” Moses asked the boy. When he didn’t answer immediately, Moses took the conversation elsewhere. “William. Or is it Bill? Oh, it doesn’t much matter, we’ll figure out your blues name. Billy Three Chord. Billy… Bill something… Now as I was saying, I came to Garfield’s Crossing as a result of an unfortunate set of circumstances. And if there’s anything Garfield’s Crossing is known for it’s being the result of an unfortunate conflux of circumstances. But I don’t want to go on and on about all that. You see, when a town prides itself on the itinerancy of a third-tier president, you know there’s an underbelly they’re trying to hide. Something really ugly.”

Two steaming Styrofoam bowls emerged from the metal door in the hands of the Shanghai-Man. Moses raised the bowl to his lips, breathed in the steam and savored. Lemongrass and mint. Cilantro and ginger. He savored this soup the way some men revel in sunrises, fine wines or orgasms, though he wasn’t especially familiar with the first two.

William did the same. The soup was fine. Delicate even, and momentarily made Moses forget he was standing in a stinking back alleyway meant only for activities that made your senses go dull. Moses began to sing:

“Blues fall mama’s child

and it tore me all upside down

Travel on, poor Bob

just cain’t turn you ‘round.”

“The blu-u-u-ues

is a low-down shakin’ chill

Throwing back his patchy, balding head, Moses closed his eyes and spoke the words, “Preach ‘em now.” Sweat rolled down his neck, disappearing behind the white shirt collar too big for his neck. And despite the choking heat, the faded black suit jacket remained over his shoulders.

“You ain’t never had ‘em, I

I hope you never will

Well, the blues

is a achin’ old heart disease

Moses rolled his head to the side, hanging it limply near his shoulder. In the same soft speech he said, “Do it, now, Moses Jones. You gon’ do it? Tell me about it,” while tapping his fingers to keep the beat on the guitar that wasn’t there. His face twisted and tightened with each pluck of an invisible string, each movement of his skeletal fingers while the other hand held the soup aloft, spilling none of it.

Let the blues

Is a low-down achin’ heart disease

Like consumption

killin’ by degrees

The bluesman mopped his brow with the back of his hand. “You should have recognized that one, son, since you’re on some kind mission yourself,” Moses said. “Robert Johnson’s got something to say to all of us.”

“That’s nice, Moses Jones,” the Shanghai-man said.

Moses paused. “It’s got to be Billy. Lot’s of great bluesman used Billy. Billy Flynn. Billy Williams. Billie Holiday, of course. Billy “Three Chord” Lancaster.”

“I said that was real nice, Moses, the Shanghai-man said again.

“Don’ butter me up so you can ask for one of your Elvis tunes, Shanghai-man.”

“I give you the soup and you play me Elvis.”

“Tomorrow, Shanghai-Man. Let Elvis rest in peace one more night. And don’t start on that notion of your that Elvis is living in a retirement home in Roswell.”

Moses stared up at the streetlight and the insects swarming in and around its sickly yellow radiance. He noticed that if you watch the bugs long enough, they attacked and returned in intricate and regular patterns, repeating the same hopeless instincts. They returned again and again until, he noticed, they’d find the crack in the casing and fry themselves. Like a moth to a flame, they got what they wanted in the end.

Moses drained the last of his soup. Handing the bowl back to Shanghai-Man he said, “But then again nobody’s guaranteed tomorrow,” and then tugged on the door. Having forgotten to replace the door brick, the metal slab, of course, didn’t budge. Moses sighed and then started off walking toward the front of the building without a word about it.

William glanced at the Shanghai-Man, still holding his nearly full bowl of soup.

“Take your time. Finish your soup. He’ll come back,” the restaurateur said.

“What’s your real name?” William asked.

“Jimmy,” the man said and then they waited silently while the kid sipped his soup. Sickly bells rattled from inside the restaurant. “Customer,” he said, shrugging an apology before disappearing inside.

William checked his watch.

The door opened. “As I was taking the long walk around the front of the building,” Moses said, ushering the boy inside, “I remembered a story. It seemed imperative to tell you what you’re getting yourself into. Now, you know I don’t much like talking about myself but this is an imperative matter. This one time, back in Clarksdale, I got replaced by a jukebox. That’s where we’re at in the 21st century. See what I’m saying, Billy “Three Chord” Lancaster? Good. Now let’s have some coffee.”

“I don’t really drink coffee, sir.”

“That’s okay. Who drinks coffee at a bar?”

Moses sat down at a table beneath a dartboard in the darkened rear corner of the blues room. Away from the stage. Away from everyone except a couple of hushed drinkers huddling over whiskey glasses – two women, one with curly red hair the color of fairytale dragons and the other pale and unremarkable. The regulars had cleared out during Moses’s soak.

“You see, nobody sits at this table on account of all the dart holes, but I’ll let you in on a little secret.” Moses leaned in. “I made them all with a utility knife. We don’t have any darts for the dart board.” He pointed out the preponderance of dart holes in the triple six. “I didn’t do these,” he said. “One guy we had in here carried a case with his own darts.”

Moses let that statement hang there, like a wisp of smoke before continuing.

“So as I was saying I was playing this club in Clarksdale. A regular gig. Steady pay plus tips. Free beer. Then a man by the name of Mr. Punkin shows up claiming to have bought the bar and told me he wanted to replace me with a jukebox. In Clarksdale, the birthplace of the blues, can you believe that? Said it was cheaper and no jukebox ever made his waitresses uncomfortable. Now that was just one occasion mind you and wasn’t none of that my fault. I’d been a fixture in Clarksdale and surrounding environs for years. Started out as a mere boy, not much older than you I wager. Learned from the best right there in that club.”

“Mr. Moses Jones, sir,” the boy said.

“Yessir, Billy ‘Three Chord.’”

“My mom says we have to go. She’s tapping her watch.”

“Go? Go where?”

“We’re on our way to Pensacola.”

“Well,” Moses said, his gaze drifting off at the warm, happy, welcoming adults standing in the archway. “In that case, I’ll look for your records, William Lancaster the third. Maybe you’ll invite me to play on your record some day. You’ll be my meal ticket during my golden years when my fingers ache from the arthritis. When I’ve got nothing left to offer of myself. When the devil’s finally taken it all.”

The boy stood and waved and awkwardly turned and joined the family with a mom, a pa, and another sprout that looked a lot like him. The nuclear unit of Lancasters shuffled out the door with angular, long-take glances that suggested they’d taken a pee without buying some fries or a Coke but thoroughly enjoyed the experience.

“Excuse me, Mr. Jones. Is that your name? Moses Jones?”

Moses Jones pronated and found the unremarkable woman addressing him while the girl with the dragon hair giggled and cowered behind her palm. Skunk drunk. Moses confirmed that his name was indeed Moses. The girl seemed to require more conversation so he obliged. “Since you know me. It’s time I knew you. What’s your name? What’s your story?”

Moses pulled up a chair.

“Tracy. And this is Emily. Just two girls with nowhere better to be at the moment.”

Moses nodded. “Sounds like you’ve got trouble with your men. Or women. I don’t mean to be presumptuous.”

“I was listening to your conversation with the boy,” she continued, “I’m sorry if I was eavesdropping a bit. It’s what I do. I’m not from around here in case you couldn’t tell by my unfamiliar face. I imagine you know just about everyone that comes in this backwoods gin joint.”

“You are a curious bird.”

“Back home they call me nebby. You heard that word? Nebby?”

Moses shook his head and said he hadn’t, but based on their conversation so far, he got the general idea.

“I heard you saying that thing about being replaced by a jukebox. Emily here was just replaced by her band – part of that guy trouble. Guy falls for girl. Guy invites girl to sing in his band. Girl turns out to be pretty good. Guy throws her out when she decides he’s a no-good scum-sucking bastard cheat screwing her friend Dorothy. But you know that old story.”

Emily nodded along with Tracy’s rendition of her facts. “It’s still pretty raw,” she whispered.

“So what happened after that rat bastard told you to hitch?” Tracy asked.

“Oh, you don’t want to hear more about that, Miss Tracy, and I really don’t want to tell you all the sordid details, but the man told me that he couldn’t have me in a bar where people wanted to play the jukebox. He said these people,” Moses held his hands aloft like Atlas, “these people here want to listen to Shania Twain when they want to listen to Shania Twain. He said that. He said people don’t want the blues no more. Not regular blues. Just ‘sometimes blues’ he called it. Like they got enough troubles, they don’t need mine on top of it.” Moses lowered his voice, like he was about to tell a dark secret. “And you know what I said to that?”

Tracy said she didn’t and learned further towards Moses across her table to hear that secret.

“‘Punkin, these people you think you know have blues in their blood. They come from all over the country, all over the world to hear the blues in Clarksdale.’ And then I did something I shouldn’t have done.”

“What did you do?”

“I told him, ‘Punkin, your daddy would whip you for saying something like that’ – you see, I knew his daddy and I knew his daddy was one hell of a bass player in a N’Orleans jazz band called the Big Trouble Bayou Band.” And after I said that he stuck his breadstick finger into my chest and said ‘Ain’t none of your business, bluesman, what my daddy would have done if he were alive.’ ‘God rest his soul,’ I say. But he goes on, ‘He was nothing to me and he was nothing to my mom and I’m going to put a jukebox back here right where you’re standing because don’t nobody need a house bluesman.’ And then he ran his fat fingers through his carroty hair plugs and told me he couldn’t pay me anyway so I might as well just leave. I stayed and finished my set, of course, because that’s what you do. People cared about those three chords whether they say so or not. I’ll never forget that piece of advice. Slide trombone player by the name of Flip Top Willie told me that in Scranton, of course, he didn’t say ‘three chords’ on top of him being a sackbut, but I understood his meaning. He said ‘You’ve got to play the songs, because it’s what you do. And they’re gonna listen, because it’s what they do.’”

Chin resting on her palm, staring enraptured, Tracy said, “You sure talk a lot for a guy that’s not too anxious to talk about himself.”

“All we can do is keep going.”

Tracy raised her glass. “Here’s to keeping going.”

“I don’t have a glass,” Moses said, tipping a hat that also wasn’t there, “but here’s to it.” Moses pressed his lips together, looked ready to say something that didn’t happen.

“Well,” he finally said, “I guess I’ll get back to my set. And don’t you worry. Aren’t none of them happy songs.”

“What you got to be sad about, bluesman?” This time it was the the flame-haired Emily that spoke. She wasn’t terse or seasoned. She was just curious, like here we are sharing this same space, the same air. We’re all talking. We’re all alive. At least that was how Moses read it anyway. Could have just been the drink in her, though, that made her seem so casual despite the heavy inquiry.

Moses thought about his answer for a moment. He didn’t want to seem premature with his answer, but yeah, he had the blues he figured. Before he could speak, however, Emily had another thought.

“Like what are the blues anyway, bluesman? Are you actually, like legit sad?”

“Well, Miss Emily. I don’t suppose it’s that simple. Being sad or not. I’ve sung a lot of sad songs. Don’t make me sad, though I suppose singing them brings me some of that catharsis. I’ve always liked that word, ‘catharsis.’ Sounds like what it means. Sounds heavy. I’ve sung a few happy songs, too. Don’t mean I’m happy neither. And they too can be cathartic in the right place and time.” He paused, without really coming to any conclusions himself. “I suppose we are what we are when we are. Maybe that’s the blues. Maybe the blues is just the forces beyond our control that drive us from place to place and person to person.”

She nodded. Was she satisfied? Or was she just waiting for more.

“Are you a pious man, Moses Jones?” Emily asked.

The question stopped Moses. “Ain’t that a $64,000 question,” he said, rubbing his chin with the back of his hand. “If I believe in evil, then I must also believe in good. But I don’t know if the church would call me pious, necessarily.”

“Why don’t you sing me some more songs and I’ll see if I can’t figure it out,” Emily said.

“I’ll sing you some songs tonight if you come back tomorrow and sing a couple songs with me. Up there on stage. One might need to be an Elvis song. Too early to tell.”

“She’ll do it,” Tracy said, jumping in before Emily had a chance to disagree.

“Perfect then.” Moses stood and wandered back towards the stage in half-steps. “And now I should get back to singing the blues because talking about the blues is like dancing with the lights off. The blues is about living and breathing.” He wondered what that meant anymore. It was something he said because he believed in it when he was younger. What was living when the world these days seemed so hell bent on extinguishing that fire? Moses pulled his chair back to the front of the stage and picked up his guitar. The strings vibrated beneath his hand, breathing all on their own. His finger rested on that feral A-string.

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen and welcome to Jenny’s Crab Shack right here in Garfield’s Crossing. Some of you are regulars – I see you back there at the bar, Marcus – but I’d wager that most of you are just passing through. I’m Moses Jones.” Moses paused for the smattering of applause, mostly from Tracy and Emily up front, “And this is Mary,” he continued, holding his guitar up. “We’re going to play you some more sad songs tonight. What do ya’ll say about that?”

Tracy clapped some more and gave a whistle that sounded more of spittle than whistle.

“Before I get going, I’d like to share a story my new friend over there, Miss Emily, reminded me of just now.” He paused, lost in his thoughts. When his voice returned it returned an octave lower. “I was walking down a street called Tallahatchie one night looking for Motel 6 and I heard a clap of thunder. I looked around and nowhere in the darkness was a neon sign. Just a cooling breeze chasing away the humidity and a Quick-Stop with a fat woman filling up her Corvair with premium unleaded.

I stepped lively when the first raindrops hit pavement. I had my guitar case and not much else and while I wasn’t afraid of getting wet myself, Mary, well, she’s not so delighted with the rain. The skies turned from black to grey and then a kind of green that I’d never known. I took my guitar case under my arm and I said, ‘Hold on, Mary, we’ve got to get you home.’ And I took off running and before I knew it was standing under a red motel awning. I pushed through the double doors. I was quite a sight. Wet as a mangy dog, smelled like one too. And do you know what the motel owner says to me? He says, ‘Looks like the devil’s doing his work out there tonight.’ I coughed and I looked at the man in the company-issued shirt behind the desk and I said, ‘What do you mean by that?’ He said, ‘It was like it just followed you in here. No warning. One minute it’s a regular muggy July evening and the next thing I know you run in carrying that guitar followed by a storm cloud the likes of which I’ve never seen around here. Maybe in Oklahoma, mind you, but not here. That’s twister weather up out of nowhere.’”

Moses cracked the knuckles on his right hand by making a kung fu fist and then releasing his fingers with a harmonic pop pop.

“And then some fellow said to me, ‘It was like the devil was chasing you, son.’ I turned and saw a man sitting in what would pass as that Motel 6 lounge, four chairs and a glass table filled with Cosmopolitans. He was wearing a fedora with a red feather and dark grey woolen suit in weather not unlike this slop we’ve got outside right now.”

A voice from the back of the bar interrupted Moses. “Why don’t you stop talking and play the guitar, bluesman?”

The man leaned on the arched doorframe holding a glass of something clear. Since the drink still contained the small red stirrer, Moses noted he’d ordered a cocktail and expected him to take a sip from said stirrer because who orders a cocktail in a blues bar? The names of songs rattling around in his head came with umbrellas and road trips and trips to free summer amphitheater shows.

“Is there something you like to hear, friend?” Moses asked, attempting to diffuse the man’s righteous indignation. This was a bar, after all. And in that bar, they served libations that made people louder and more intolerable than they would normally be. Moses always thought about these people and about how unhappy they were with their lives outside the bar, but mostly he was happy the bar didn’t have darts for the dartboard.

“Why don’t you play us some ‘Rockin’ Chair,’ bluesman. You know how I like that one.”

Now those words took Moses Jones’ breath and punched it right out of his belly. Nobody requested ‘Rockin’ Chair” but one man. The same man that liked to end every one of his sets with ‘Rockin’ Chair.’

Moses squinted through the haze of the half-full blues bar, shielding the lights with his hand. He focused on the man’s headwear. A Fedora with a red feather. “That you, Stagger?”

“Play the song, Mose.”

“Damn, fool,” Moses said, smiling, suddenly with the nerves like he’d never known. “I’ll play your song. Damn. Poppin’ up like Betelgeuse after I mention you in my story. Can’t tell me that’s not creepy,” Moses muttered. The bluesman closes his eyes, touched the strings, and began to play.

“All my friends tell me, tell me.

I just waste my tears on you

All my friends tell me, tell me, tell me,

I just waste my tears on you

No, no, no, no, no…

Gonna keep on trying, keep on try, try…

tryin’ to rock these blues away.

He hadn’t played the song in years, but the words came flooding back. Moses pushed up with his toes and back to his chair, embracing the rhythms of the song. “Rockin’ Chair” was the first song he ever played for a crowd, a crowd of people checking into a Motel 6. Nothing more than a child, playing the songs he knew because of his momma’s records. The song had belonged to John Lee Hooker, but in that moment, in that Motel 6 it belonged to Moses Jones. No two men felt the same way about a song. This one, about a man trying to recover and forget love and carry on with the simple pleasures of breathing and getting out of bed, carried universal. Each man loved differently and each man mourned differently. That was the love. And that was the rock, rock, rock of the John Lee Hooker rockin’ chair.

When he was through with his set of five or six songs, Moses waved Stagger and his sipping cocktail over to his table by the dartboard.

The two men embraced. They spoke not a word and sat down across from each other. “Stagger” Lee Perry looked like an old man, at least up close and away from the harsh overhead lights. He’d aged well, Moses thought, but better from a distance. Stagger removed his fedora. The grey mingled only around his temples. The hairline holding firm. Only in his eyes did he look weary. Then again, everyone looked weary when you went looking for it. Moses wondered how he looked to Stagger, whether he too looked older, rougher, but that was just the unwelcome vanity of age, the pains of living.

“What the hell are you drinking, Stagger?”

“Club soda with a lime. You look good, Mose.”

“Like 1992, Stagger.”

“I didn’t mean to interrupt you,” he said, “but I couldn’t help myself. You always did talk too damn much.” He started laughing and covered his mouth like he was sorry, but not so sorry he couldn’t laugh. “I don’t know how your landlord feels and didn’t want to get you in trouble none. Say, Mose, how’d you get a steady gig at a crab shack that doesn’t even sell crabs. That’s a new one for me.”

“Landlord’s fine. Never mind her,” he said. “What about you? What you doin’ in Garfield’s Crossing? You swore to me that you’d never set foot in this swamp again.”

“Headin’ somewhere else.”

“Aren’t we all?”

“Hard to get to Florida without seeing the Georgia sights.”

“Shoot, Stagger. The only thing worse than Georgia in July is that gator farm down south. You still trying to play that golf?”

“Nah. Gave that up.”

The two turned inward. Silence. The ice shifted in Stagger’s glass. It had been years, decades even, since Moses and Stagger had last shared the stage in Clarksdale. At one point, Moses Jones had known every story Stagger Lee ever told and vice versa. They’d take a bullet for the other, but they were strangers nonetheless. Stagger was never a sharing man.

“I haven’t laid eyes on you since—“

“December of 1994. It was hot. Too damn hot for Christmas decorations, but the place had twinkle lights up. We’d been jumping around Mississippi. Looking for a place to hang our hats.”

“I remember that much,” Moses said.

“The day I took the last train.” Stagger looked away, up toward the dartboard full of false warnings.

“Wasn’t nothing, Stagger.” He paused. “No. That’s a lie. I’m not sure I ever really forgave you for reading the writing on the wall and then keeping it to yourself.”

“It damn well better be a lie. I’ve been sick in my gut thinking about that night. And you’re probably still wondering about a few things. And wasn’t no great plan either.”

“I’m not even going to fake it, Stagger. I called up your sister around that next Christmas to wish her a Merry Merry and she told me where you’d gone. Headed up to Detroit because turned out you were a daddy. And now your son’s a daddy and living up in Dearborn Heights. Nothing to tell. Nothing to apologize for.”

“Sis never said she was talking to you all these years. Gonna have to have a talk with her about that,” he said with no shortage of humility. “What about you? Now I’m the one who’s feeling cheated.”

“I told her not to tell. I told her I didn’t want you to know I was checking up on you. Plus, you know I crushed hard on that girl. Never gave me the time of day unless I was talking about her baby brother Stagger.” Moses’ voice trailed away in the past. “But me? Nah. You don’t want to hear much about that… but so long as you’re asking… after Mississippi, I went to the crossroads after Punkin curbed me. Like I always said I would do.” Moses picked at an etching on the table. P.E. hearted B.C. The center of the heart had been picked away by Moses’ idle fingers. “I was lost. You were the bluesman, Stagger. I was the rhythm. Without you, I knew I didn’t have the stick.”

Stagger started to interrupt, but Moses wasn’t having it.

“Nah, nah, nah. Don’t pretend otherwise. I know. You took me under and taught me what to do with all those songs I knew. I could play. Oh I could play, but what do you do with any of it. What did I have to offer?”

“Well? Don’t keep me in suspense then. What did you find at the crossroads? Did you find him?” Stagger laughed. He never took that story seriously.

Moses leaned back in his chair and considered what he’d found. He’d never actually asked himself. Not really. Course, what he knew about that day now wasn’t what he knew then.

“If Robert Johnson found the devil and sold him his soul for his ability to play guitar, then the devil was full up of souls because Robert Johnson’s nourished him good. I stood at that intersection for an afternoon in that beating sun.

“I took turns at each corner. Standing around and kicking pebbles until sometime around seven. I saw this big black car coming way off in the distance and I thought to myself that the devil sure was minding the speed limit. When the car finally caught up, I saw the car wasn’t even black. It was something of a navy blue. Real pleasant looking. And the devil wasn’t the devil, just a family from Texas looking for the highway. They asked if I needed a lift. Nice folks. Rode me into Georgia. Bought me a meal, and I gave them all the money I had in the world to help pay for their gas. Wasn’t much, mind you, but it was something. The tips from my last few gigs.”

“So you’ve still got your soul,” Stagger said. “That’s fine.”

“But the devil’s still watchin’.” Moses pointed to the dart board and the corroded triple six segment. It’s not that he didn’t show. He was there all along. He’s always been there. Clarksdale. Rosedale. Garfield’s Crossing. Here in Jenny’s Crab Shack. Even up there in Philadelphia. At night I yell at the devil in my sleep. I say, ‘Devil, you come out and you tell me what you want from me!’ but the devil don’t show. And my woman she rolls me over onto my other side because that calms me down. Sometimes sings me a lullaby.”

She sings, ‘I gave my love a cherry that had no stone. I gave my love a chicken that had no bone. I told my love a story that had no end.’ There’s more but that’s all I remember.”

“That’s lovely.”

“It is. She’s a lovely girl. Better to me than anyone in this world, but that’s the trouble.”

The two old friends talked a bit more. Stagger talked about being a daddy and going back home to Detroit, how he felt like he was living in the ghost of his own home, a once vibrant community where soul had a home. “And the soul’s all but gone now,” he said, “but there’s still Greek pizza.”

Moses nodded, but he didn’t really understand because he’d never really gone home or had Greek pizza. Home was too scary a thought after so many years away. How could he ever go back north? They went on to talk about the blues, new artists they liked, old ones that had passed. They raised a glass to the late John Lee Hooker. And then the two friends departed. Stagger excusing himself because he had a long day on the road tomorrow and because his wife was waiting for him back at the motel and probably worried he got lost.

“Good seeing you, Mose,” he said. “Keep in touch this time, huh?”

“You keep in touch. I get Christmas cards from Jolene.”

Jenny’s had mostly cleared out except for a few bleary-eyed stragglers at the bar. Tracy and Emily, whoever they were, had gone without so much as a tap on the shoulder. He wouldn’t see them again. Not tomorrow. Not any other day. Waitresses wiped down the tables. Moses returned to the stage and packed up Mary. “Wasn’t much of a night,” he said to her, “but it was another one.” He cleared the tips out of the spittoon. A note had been paper-clipped to a five-dollar bill. “Tomorrow—sing a happy song for me,” it read. Signed, “Miss Emily.”

Moses put the fiver and the note in his wallet along with the other 37 in cash. The lights shut down with a mechanical bang. The absence of the buzzing ballasts resonated more loudly. He sat there, staring into the darkness with his guitar lying across his lap. Moses ran his finger over the rips and tears in the case. One gash from a knife fight he stumbled into. Another when a guy tried to take the case while he was busking in Jackson. He’d caught him a couple blocks later, tripped him into a pile of garbage cans and got one night in the hole for assault. Moses’ eyes began to adjust. He kept searching the dark corners, the silhouettes of the waitresses counting their tips and talking about their after-hour plans at the bar. The barman wiping down the wood with his can of polish, tuning his instrument in his own way. A shadow approached, slowly, like that black sedan, miles off. The bluesman awaited his final call.

“You know I’m not really the devil,” the shadow said. “You best know that by now, but I’m not so sure, because you keep saying it to anyone that’ll listen.”

“Jenny, my love, out of obligation to the trade of the blues, you are indeed the devil. You’re my boss. You’re my woman. If he’s anywhere, the devil’s in your hips and in your eyes. He’s in that wrinkle at the bottom of your chin. And he’s most definitely in the freckle just below–”

“So who was that man you were talking with for the last couple hours?” She interrupted. “I can’t get you to talk to me longer than it takes to sing one of your songs.”

“That’s nothing but the past, but as long as you’re asking that was the man they call Stagger. And once upon a time he called me his ‘meal ticket.’ Up until he decided I wasn’t. Said I could mint him money if we stuck together… he said this to me in an old ratty motel in the middle of a rainstorm. The old bluesman and the kid with the fresh riff. But then he took off, chasing something else.”

“Did you?”

“What?”

“Mint him money? And if so, how come you ain’t doing the same for me?”

“I bought him breakfast once, but you wouldn’t be much interested in hearing about the night Stagger and I got drunk and ended up in Missoula with four undersized Large-mouth bass in the trunk and a Montana Fish and Game warden on our tail.”

“You can tell me while we fall asleep.”

“Woman, you never stay awake long enough for the twist. You never know how my stories end.”

“Moses Jones. None of your stories have an ending.”

“This one might. You never know.”