In July of 2002, Tom Hanks sat next to me at a round table in the conference hall of the Ritz-Carlton Chicago and talked about the particular demands of acting in comedies versus dramas. I asked this question because I’d been assigned the story, but I wasn’t especially interested in his response. It was, after all, being recorded on cassette tape. I could transcribe it all on the plane back home. Naturally he’d focused on the rewards of acting in dramatic fare (the specifics elude me all these years later) and the opportunity to act opposite Paul Newman. He said all the things he needed to say because Tom Hanks was (and still is, as far as I know) the consummate professional Hollywood actor.

Part of that consummate professionalism required him to promote his current film and say glowing, positive, effervescent things about Road to Perdition. The last thing anyone expected him to say was that this gig was merely the culmination of his master plan to create a gleaming, golden coffee table with Oscar-statue legs for his sitting room. Tom Hanks punched his time card like a pro; I had amateur stenciled across my forehead. I hoped I’d get to ask a second question before getting sandbagged by everyone else’s agenda.

Little did I know I was about to get sandbagged by my own agenda. I’d written for InSite Magazine for almost a year at this point. My editor took the choice assignments while I reviewed the latest Not Another Teen Movie or Ballistic: Ecks vs. Sever. Just a couple months earlier, my editor had handed me my first talent interview because, he said to the best of my recollection, “I handled bad movies with the respect they deserved.” I still have no idea if that was an actual compliment. As a 23-year-old writer who believed quite highly in himself and pined for any shred of (due) enthusiasm over my writing, I stitched that merit badge on my canvas messenger bag.

The interview? Quite predictably I’d been tasked with discussing a C-grade movie, albeit with a notable commodity. Fresh off Rushmore Jason Schwartzman made a pond dredge teen movie called Slackers. In case the “pond dredge” comment wasn’t leading enough, I’ll say it plain: Slackers stunk. When he made a joke about my Gap jacket, I’d been so focused on obscuring how much I hated the film that I failed to come up with any rebuttal.

I still regret the zinger I never made. I replace the tags so not to intimidate my interview subjects with the posh lifestyle of a tabloid-format journalist. Maybe not the ultimate burn, but still better than a nervous laugh that surely betrayed the fact that I took his crack about “having that same jacket” seriously for an embarrassing number of seconds. Welcome to the business, you’ve just been roasted by a snarky actor two years your junior. I just wanted to conduct the interview and vacate the hotel suite before someone faxed him my D-grade review. It also wouldn’t be the last time I regretted questions or thoughts left unsaid in an interview.

Determined to not repeat past failures, failed to hear the entirety of Mr. Hanks’ response before firing off a second question, or rather a leading statement, which was really the question I’d been dying to ask all along. I said, “I actually consider it a shame that you’ve turned your attention away from comedy because I consider Joe Versus the Volcano the most important movie you’ve made.”

He paused, befuddled perhaps, and regarded this petulant whippersnapper (as I’m sure Tom Hanks’ internal monologue uses words like “whippersnapper”) with some sense of dismay and concern, brow furrowed at a gently sloping 45-degree angle. Was I confused? Impaired? Should security be called? Who was I to suggest that some silly movie he made way back in 1990 was better than award bait like Philadelphia, better than Saving Private Ryan and Forrest Gump, better even than the movie we’d all just watched, which was the most impactful movie in the history of cinema for the duration of this particular gladhand? Surely I’d prefer to assuage his ego about his latest most important accomplishment.

Ultimately, he laughed and thanked me for the sentiment, but did not specifically address my claim about Joe Versus the Volcano before others around the table began lobbing their favorite comedies like holy hand grenades from the trenches, making sure the actor had duly noted each of their picks, all of which seemed like an entire career ago. Someone mentioned Splash and Bachelor Party. Big came up. One of the guys even dropped The Man with One Red Shoe. I’d love to recast the table with at least one woman (because equal opportunity memoirism matters) so we’ll say this hypothetical woman mentioned Joe Dante’s The ‘burbs because The ‘burbs is also terminally underrated and this fictional ‘she’ would have had the good sense to make mention of it.

Nobody else, however, corroborated or acknowledged my Joe Versus the Volcano sentiment.

As our time with the actor ended, and as Mr. Hanks stood to move on to the next table, I asked him to sign my Road to Perdition pressbook. I’d never asked anything of any of the dozen celebrities I’d interviewed. These were just men and women doing their jobs who also happened to be household names. We were just doing ours. Some of us even got paid for it, but nobody knew our names. All of the other on-screen talent I’d interviewed had duly reinforced their celebrity status. Lists of things that couldn’t be asked, warnings about certain lines of questioning, untimely entrances and unusual water concoctions in pitchers provided by personal staffmembers.

Tom Hanks fulfilled every fantasy about Tom Hanks — cordial and friendly and inclusive. He happily signed my pressbook and all others at the table. He treated each of us like old friends and then abruptly exited our lives. Yet he never calls. He never writes.

On my flight home I began to transcribe the interview and I finally stepped out from behind the glow of conversing with Tom Hanks. I recognized how deftly he’d sidestepped my comment about Joe Versus the Volcano by responding modestly and without haste, thereby inviting others to chime in and dilute the precision of the question. A diabolical counterattack. His lack of displayed ego, coupled with the enthusiasm of the gathered round table allowed my Joe Versus the Volcano comment to dissipate without a trace, much like the movie itself in March of 1990.

If Tom Hanks didn’t see beyond the lackluster box office numbers, the confused moviegoing masses, and the unshakable scarlet “B” for bomb; what hope did anyone else have? Did he not think as highly of it as I’d assumed? Who else out there saw Joe Versus the Volcano for what it really was? Surely he could see that the real bomb wasn’t Joe Versus the Volcano at all, but The Bonfire of the Vanities, which kindly supplanted Joe as the headlining disaster on Mr. Hanks’ resume.

My mind raced with all the questions I didn’t ask, that I couldn’t ask. If only I’d had ten minutes to clarify his stance on this very important issue. I’d ask him about John Patrick Shanley’s script, about working with him as a first time director. How the chemistry between he and Meg Ryan eventually gave birth to the mega-hit Sleepless in Seattle. Did they see the eccentric beauty on the pages of the script? The novelty of philosophy? What registered with audiences beyond the jokes and face-value absurdity of a tribe of Celtic/Jewish/Roman/South Pacific islanders obsessed with orange soda and governed by Abe Vigoda needing a willing sacrifice to the Great Woo?

Alas, Joe Versus the Volcano remains an underseen gem that seems to just keep carrying on in the margins of film appreciation. To call it a cult film feels rather anomalous. Joe Versus the Volcano was a $25million Hollywood production fronted by two of 1990’s biggest stars that one and a half times recouped its budget, but it still can’t shake that stigma of failure.

The term “cult” has typically been reserved for films such as Eraserhead, Repo Man, Donnie Darko, weird movies, beyond the fringe movies, movies that evaded commercial acceptance because they shunned mass appeal in favor of some sort of eccentric or singular vision – be it a failed artistic enterprise or misunderstood genius. The term encompasses massive misfires that have come to be enjoyed ironically and films that took a circuitous route to find a small, but devoted fanbase. Rarely does the term “cult” find assignation on a big budget mainstream semi-success mislabeled a bust. It was viewed by a great many and still written off as an ephemeral trifle. Vincent Canby, the longtime critic for the New York Times likened its misfire to that of Howard the Duck and called it “theoretically comic” and a “mixture of comedy, fantasy and mock-dirge.” He wasn’t alone in that sentiment.

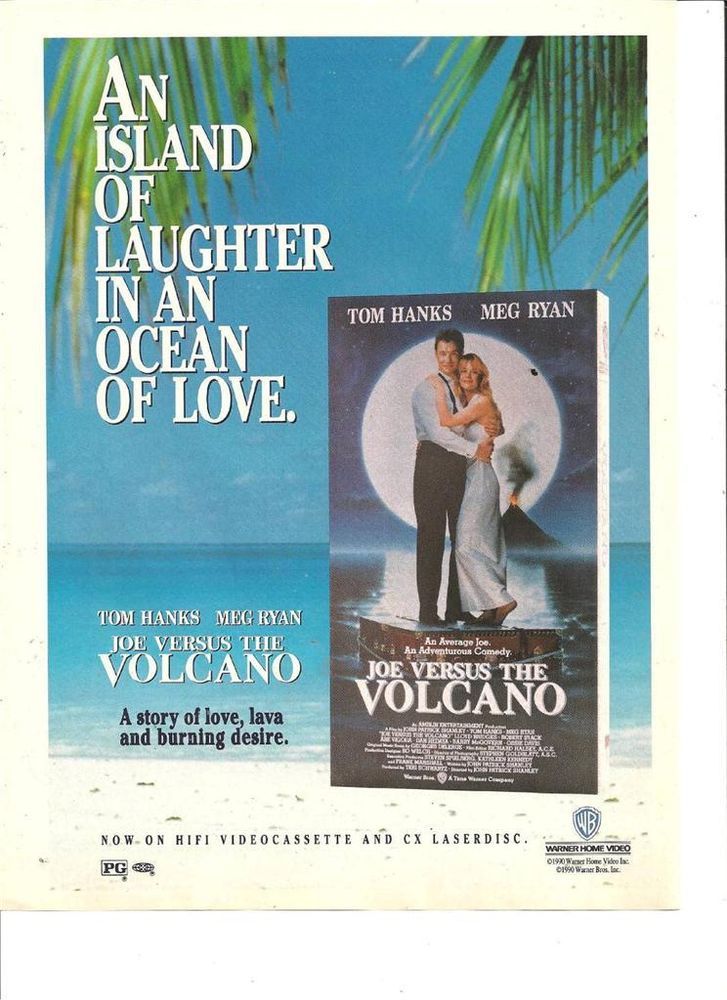

Joe went to work. Joe hated every minute of it. His only escape from this circle of hell was the recognition of his own imminent death. The acknowledgment of his own mortality grants Joe Banks a second chance at life. The most damning thing about Joe Versus the Volcano was that it just wasn’t what anyone expected because it wasn’t really like anything we’d ever seen. The film’s marketing embraced the rom-commy coupling of Tom Hanks and Meg Ryan because they didn’t know how to construct a marketing campaign that sold anything but the reputation of its stars.

It looked like puerile comedy. Many critics likewise called it a simplistic oddity or a trifle. I’ve always been unable to fully grasp how so many critics seemed to have watched a completely different film. Now, having written about film on and off for the last twenty years, I understand more fully how something so stunningly original could slip through the cracks and become misunderstood. Rotten Tomatoes didn’t exist in 1990, but the critical consensus still imposed its will upon the box office, leading all of its witnesses to the same conclusion.

Would a trifle of a film dare to examine commercialism, the soul-crushing burdens of adulthood? Could a “flat” film deftly champion spiritualism while undermining organized religion? It astounds me that a movie with so much individualism and eccentricity could be read as having nothing interesting to say. Joe Versus the Volcano wasn’t a silly romantic comedy as advertised in the trailer, as expected by everyone that walked into the theater; it was a darkly comic fable about the value of agnosticism, about using the awareness of mortality as raison d’être.

These misconceptions have hindered the film’s rediscovery more than any other factor. “Odd,” “bizarre,” “weird” – these are terms that pique a cinephile’s curiosity about movies on the fringe. Terms like “trite” or “flat” or worst of all, “boring” sentence a film to the very real cinematic purgatory reserved for something like that Matthew Broderick vehicle Out on a Limb from 1992. (Stephen Holden correctly called it “frantically unfunny.”) The ripples from which stopped being felt the minute that VHS tape disappeared from the New Release section of your video store. It slipped into total obscurity not because it was unfunny, but because it wasn’t incompetent and/or bold enough in its failure to warrant curiosity.

It’s a very real possibility that John Patrick Shanley’s film could never have found success. For years I bemoaned the film’s reception and how it likely derailed Shanley’s film career. After all, we want these daring writers and filmmakers to be rewarded for their efforts. These films mean something special to us, so why shouldn’t they duly reward their creators? But what if John Patrick Shanley never anticipated or even craved commercial success? In comments about his experience in Hollywood, the playwright has suggested that the filmmaking gig was not an ideal match for his personality. He called the moviemaking industry “antithetical” to his nature and seemed more than happy to abandon it and return to writing and directing for the stage – a situation that the perceived failure of Joe Versus the Volcano surely expedited.

In a perfect world, our favorite films make billions of dollars, and studios give people like John Patrick Shanley unlimited budgets to make any film they want in perpetuity. Shanley’s Academy Award for writing Moonstruck, allowed him to make Joe Versus the Volcano, an eccentric passion project. And just like that his meteoric and circuitous career trajectory from playwright to failed Amblin Entertainment-backed auteur and back to playwright had been completed in a little under three years.

Alas, it is and forever will be the way of the world. When movies dare to be something beyond expectation, they risk commercial failure. Great movies often, however, eventually find their audience. Many people forget that John Carpenter’s The Thing and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner were both box office disasters before they became certifiable classics of their respective genres. Their only mistake was appearing in theaters the week after Spielberg released E.T.

Carpenter and Scott eventually found their audience, but I can’t necessarily say the same about Joe Versus the Volcano. Unlike those films, Joe wasn’t merely obscured by an unfortunate release date. While the specter of Pretty Woman looms large in the Joe Versus the Volcano story, I can’t actually blame the film’s relative obscurity on a Julia Roberts’ starmaking vehicle (although I desperately want to).

In the end, perhaps a comedy rooted so deeply in the philosophy of our very existence could never have hoped for anything but adoration from the cult of a few impassioned fans.

Joe Versus the Volcano opened the 2012 Ebertfest. That might even surprise the most devoted fans of the film. Roger Ebert had been one of film’s earliest champions. He wrote in advance of Joe’s screening “I continue to believe it deserves greater recognition, and cannot understand why I gave it 3.5 stars instead of 4.” Great films need champions and certain great films need even more championing.

This isn’t a call to right the egregious wrongs of a prior generation of moviegoers – this is a suggestion that Joe Versus the Volcano has something important to convey to all of us and maybe, just maybe, the world would be a better place if everyone had a copy of the movie of their shelf and took to heart the message contained within.

Yes. Joe Versus the Volcano deserves consideration alongside such quirky cinematic classics like Harvey or The Princess Bride. I believe this in my bone marrow. I also have to consider whether widespread notoriety or acceptance benefits every movie. Does Joe Versus the Volcano mean so much to me because it’s not widely considered a classic? How would my perception of the film change if everyone believed, as I do, that it’s a near-perfect modern masterpiece? Compare it to the aforementioned The Princess Bride, which is similarly quirky and magical and funny, but broadly consumable, whereas Joe dares to analyze the human condition.

Assessing what makes Joe Versus the Volcano unique requires an evaluation about how we feel about life and death and religion and our ability to affect change – not exactly comfort viewing if you peel apart the film’s whimsical external layers. To those unwilling to take that plunge with Joe to appease the Great Woo, it makes perfect sense that the film would seem like trite entertainment. Joe Versus the Volcano has never been more relevant than it is today, but is a modern re-evaluation even possible when mainstream audiences seem more intent than ever to insulate themselves from meaning?

Some movies become cult films because they can’t be anything else. Does the art of being a cult film have more to do with the ways in which they connect so viscerally with a small percentage of people? Maybe Joe’s greatest purpose was this connection – this major importance to a minor few. I decided it was important to find out by digging into John Patrick Shanley’s philosophy, to consider the reasons that certain people connect to the film so deeply and analyzing how my own affection has changed and evolved with my own greater perspective accumulated during the last 30 years.

I’ve also written blurbs about Joe Versus the Volcano for Inside the Envelope: The Netflix DVD blog and Rupert Pupkin Speaks.

This (hopefully) is the first of a multi-part series on Joe Versus the Volcano. If you’ve yet to take your first plunge into the volcano with Joe Banks, pick up the Warner Archive Blu-ray. Support Joe and the Archive.

James David Patrick is a writer. He’s written just about everything at some point or another. Add this nonsense to the list. Follow his blog at www.thirtyhertzrumble.com and find him on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook.