During recent Stanley Cup Final broadcasts, NBC broadcaster Doc Emrick plugged The Mummy (2017) with the assertion that the Mummy has (and I’m paraphrasing here because I wasn’t taking movie notes about this Mummy article during a hockey game) “terrified and fascinated humanity throughout the millennia.” He’s of course making a glib, studio-prescribed sales pitch that highlights the fact that mummies are really old.

I love deflating these prosaic platitudes with darts of reality.

The History of the Mummy Movie Monster

To be more specific, the ad men are saying that the Egyptian mummification process first appeared on the historical record circa 3400 BCE – and “true mummification” using evisceration techniques (removal of the vital organs) began circa 2600 BCE. This means that these shrouded monsters officially began terrorizing fragile moviegoer constitutions starting around 2600 BCE! Clever!

The Mummy as a fictional monster didn’t appear, however, until 1932 during the first Universal horror cycle under studio founder Carl Laemmle and that of his wide-eyed and eccentric son and head of production Carl Laemmle, Jr. Even though Mummies time somewhere between the Blob and Zombies on their rates of attack, the cinematic Mummies in question didn’t literally take 4000 years to reach multiplexes near you – not even with Tom Cruise and his baggage in tow.

Instead of merely offering hokey studio taglines some side-eye, let’s look at the actual genesis for the Mummy monster. Even though the Mummy seems like such a natural villain, the journey from sarcophagus to movie immortality was hardly predestined. Three primary events came together at just the right time to inspire Universal’s wildly successful The Mummy in 1932.

The success of Dracula (1931).

German expressionism ushered in a new era of visual storytelling. Dramatic, high contrast cinematography, gothic surrealism and the ultimate import of these filmmakers, like Paul Leni, shifted the visual landscape of American film in the early 1930’s.

Few pundits believed American audiences were ready for a deadly serious, full-length supernatural horror film. At the time of its release Dracula was considered an enormous risk, despite the cultural acceptance of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel into the public conscience. And although America had reacted positively to silent thrillers like The Cat and the Canary (1927, directed for Universal by the aforementioned import Paul Leni), Dracula would not pull back the curtain to reveal a trick ending or comic relief. Until now the “Scooby-Doo ending” had been a common tool to delegitimize the supernatural elements and release the viewer from the on-screen terror.

William Henry Pratt, aka Boris Karloff.

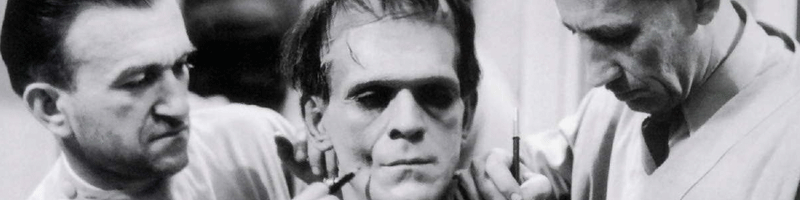

One story suggests that James Whale’s domestic partner, David Lewis, saw the actor in the stage production of The Criminal Code and recommended him to Whale for the role of the monster in Frankenstein. At this point, Karloff had been toiling in Hollywood anonymity for about 15 years. Even at 5’11”, Karloff projected the physicality and provided a countenance that had been lacking in other actors testing for the part. Karloff plus John P. Pierce’s makeup equaled movie magic.

Variety called Karloff’s performance “a fascinating acting bit of mesmerism,” and the film went on to become the highest grossing film of 1932. Universal immediately wanted to find a new vehicle for the buzzy actor, billed then as “Karloff the Uncanny.” The studio went forward with a story by Nina Wilcox Putnam and Universal’s story editor Richard Schayer called “Cagliostro” about an immortal man who’d lived through many millennia. With rewrites by John L. Balderson (who’d written a stageplay called Berkeley Square that concerned a romance across the ages) based on recent events, the immortal European wanderer became an undead high priest of Ancient Egypt.

The 1922 discovery of Pharoah Tutankhamun.

Archaeologist Howard Carter and financier Lord Carnarvon explored the Valley of the Kings in Egypt for more than a decade before finding the burial chamber of King Tutankhamun. The discovery ignited a very public obsession with Ancient Egypt. The King Tut craze inspired songs, movies, and the name of President Herbert Hoover’s Belgian Shepherd. The mysterious deaths of some of those involved in the tomb’s excavation resulted in the legend that has become known as the “curse of the pharaohs” – the perfect real-life fuel for cinematic nightmares.

The Rise of the Mummy

In the hierarchy of classic monsters, the Mummy often takes a backseat to Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster and the Wolf Man. Vampires are sexy. Frankenstein features the re-animation of parts from dead people using lightning. Lycanthropy even sounds snazzy and legitimately science-y.

The terror of the Mummy, meanwhile, took the form of a shrouded monster in raggedy bandages that wandered around (slowly) picking off those that dared interrupt his beauty sleep. (In many ways, the Mummy became a proto-zombie figure.) Someone inevitably doubts the legend and reads a forbidden scroll and so on and so forth. It’s all very formulaic and predictable – when you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all. It’s not a stretch to consider the Mummy Universal’s least loved monster.

Now that I’ve sufficiently lowered expectations, let’s circle back so I can explain all the reasons why the Mummy became my personal favorite of the classic Universal horror franchises.

The Universal Mummy franchise lacked the dramatic highs of the Frankenstein series or the legendary countenance of Bela Lugosi, but consistently churned out a capable mixture of chills, romance, and eventually humor through six Universal-produced films between 1932 and 1944. Highlights include the elaborate and exotic set design, Jack P. Pierce’s painstaking makeup effects, and innovative variations on a narrow thematic bandwidth.

Like the other Universal horror films, The Mummy (originally titled Im-Ho-Tep) relied on mood and setting. There’s nothing face value terrifying about these films, but they burrow under your skin for reasons other than their fright-factor. As a kid the Mummy ignited my imagination in ways that the other movie monsters couldn’t. I’d dream of exploring ancient tombs or discovering spiritual artifacts that could resurrect the pharaohs. Meanwhile, I recoiled at the thought of dissecting a frog so no part of me wanted to deal with cadaver bits. And what kind of fresh nonsense was a man that turned into a wolf during a full moon? What about heavy cloud cover? And what would a lunar eclipse do to his disposition? For whatever reason, I’ve always found the Wolf Man a more problematic transformation than Gremlins.

The Mummy had magic, mystique and romance. Within the tattered bandages and decomposing flesh lived the beating heart of a romantic. The resurrected walking corpse almost always had love on his mind – the kind of timeless love that spans multiple regenerations. He’s really just a Romeo with an unfortunate hobby of homicide. Like the other monsters, he was just a little misunderstood.

To read more about the Universal Horror Monsters, I recommend the following books:

And in case you missed it, Universal just released the Mummy Legacy Collection on Blu-ray.