There’s a reason 1989 looms so large – not just in my own esteem, but also for the movie business itself. It’s as if 1989 represented a kind of temporal fulcrum, like Back to the Future’s October 21st, 1985. The future of the film industry was not yet written. The novelty of sell-through home video (priced for purchase at $30 or less rather than $80-$100) had shortened theatrical release windows. Media conglomerates had begun devouring the Big Six studios. Sequels and franchise films dominated the landscape, predicting the coming wave of globally-relevant, serialized entertainment.

To quote Joe Banks in Joe Versus the Volcano (unfortunately a 1990 film – but still relevant), “I didn’t know it—but I knew it.” Even if I didn’t know why 1989 felt so important, I could feel the revolution in the air. I knew this was a great time to be a movie fan, but I didn’t know it wouldn’t last. If you weren’t yet of moviewatching age or have just forgotten, allow me to be your guide through those magical summer months.

(This is an abbreviated travelogue, culled from other writings I’ve done about the Summer of 1989. See the latest here.)

April

I’m stretching the boundaries of the season because the Boys of Summer start their season in April. During April of 1989, the multiplexes treated us to two baseball movies that would go on to become genre staples. Even though the weather outside probably didn’t scream sunshades and umbrella drinks, studios had already thrown out the first pitch. Play ball.

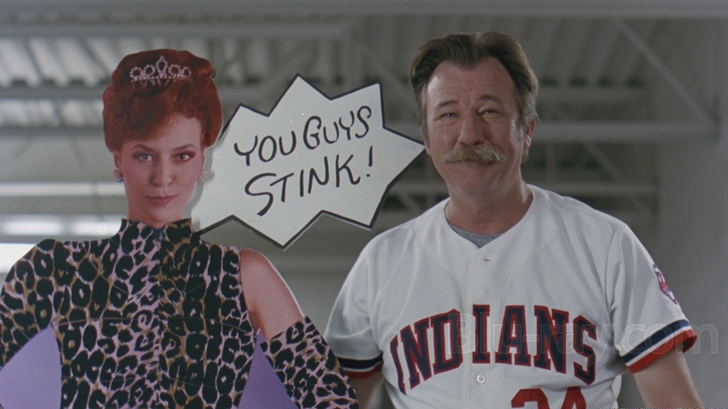

MAJOR LEAGUE (David S. Ward) – April 7, 1989

The pro-ball retelling of The Bad News Bears strikes a unique balance between screwball and sentimentality (but mostly screwballs and wedgeheads). Dennis Haysbert’s voodoo slugger sacrifices chickens to power his bat and, on the other end of the spectrum, Tom Berenger’s Jake Taylor is looking at his career in the rearview mirror and taking stock of the things he’s sacrificed to get one last shot with this team of misfits and eccentrics. Endlessly quotable and filled with wonderful comedic performances from a wide cast of professional character actors and A-list notables (including Rene Russo, Wesley Snipes, Corbin Bernsen, Margaret Whitton, James Gammon, etc.), Major League never fails to entertain. Try not to emote when Charlie Sheen comes storming out of the bullpen to a stadium singing “Wild Thing” to face Yankee nemesis Clu Heywood.

FIELD OF DREAMS (Phil Alden Robinson) – April 21, 1989

It’s too easy to write off Field of Dreams as sentimental button pushing. Fathers and sons and baseball nostalgia and purity of the game wrapped into a bittersweet weepy about whispery voices that convinces an Iowa farmer (Kevin Costner) to build a baseball diamond in the middle of a cornfield.

Boosted by wonderful supporting performances from Ray Liotta, James Earl Jones, Burt Lancaster and Frank Whaley, Field of Dreams has duly earned its status as perhaps the great modern baseball movie. But it’s so much more than just a simple baseball movie. It’s a brave film that dares to appear face-value ridiculous, a statement about imagination and nostalgic romance, the kind of movie Frank Capra would have made with Jimmy Stewart. No conversation about 1989 would be complete without it.

Elsewhere in April 1989…

Michael Keaton and a crew of mismatched mental patients attempt to take in a Yankees game in The Dream Team, John Cusack hoists a boombox for love in Say Anything…, Teen Witch begins its journey to cult classic, Mary Lambert’s adaptation of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary spooks audiences and becomes a surprise hit, and Sam Neill and Nicole Kidman battle crazy Billy Zane in the chilling Dead Calm. With at least 20! new theatrical releases during April of 1989, you’re excused for missing out on some of this underseen excellence.

May

Nobody wanted to release their movies anywhere near Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, so the first official summer movie month sputtered to a start. If you just had your calendars blocked off for blockbusters you might have overlooked some rough gems like Geena Davis and Jim Carrey in Earth Girls Are Easy, Savage Steve Holland’s How I Got into College, and Fright Night Part 2.

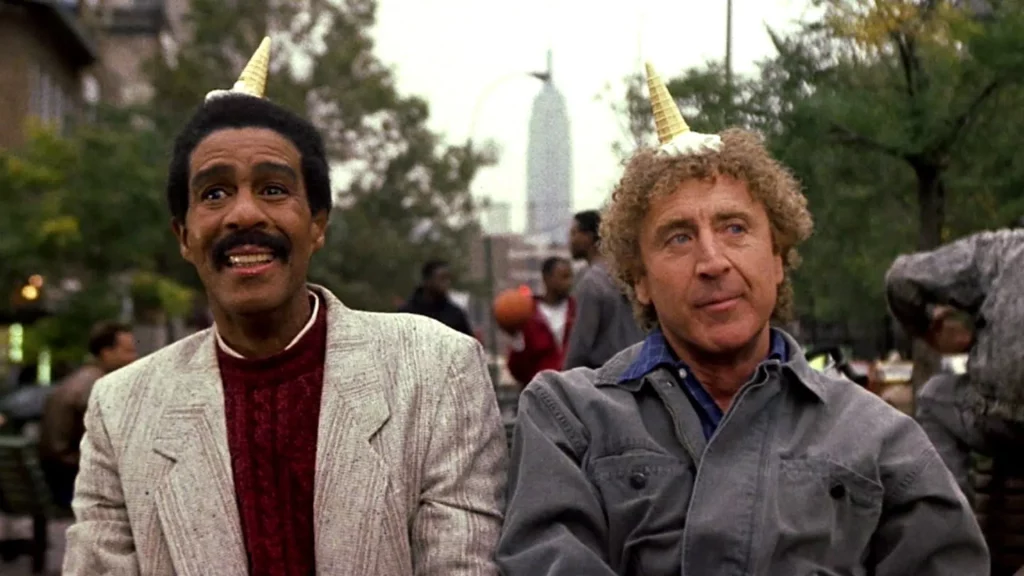

SEE NO EVIL, HEAR NO EVIL (Arthur Hiller) – May 12, 1989

Ebert called it “a real dud.” Various publications called it “idiotic,” “stupid” and “contrived.” That may be, but the combined powers of Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder (in their third pairing) can make anything worthwhile. Despite that critical drubbing, See No Evil went on to become the first semi-hit of the summer, earning more than $40 million in 8 weeks.

In a summer of megahits and cult favorites, this silly comedy about a blind man and a deaf kiosk owner thwarting murderous thieves in order to clear their names might not seem like an obvious selection. As the first official 1989 summer success, it warrants mention – but also because it’s just a fun screwball premise. A recent rewatch reminded how magical Pryor and Wilder could be when they find their groove on a simple gag. Look no further than their first exchange at the kiosk when neither knows about the other’s handicap.

Elsewhere in May 1989…

A few unfortunates opened in May before Indiana Jones rampaged through theaters. (Patrick Swayze in Road House!) Obviously, Henry Jones, Jr. duly entertains, but I’d like to spend some more time with another little miracle you definitely missed…

MIRACLE MILE (Steven De Jarnatt) – May 19, 1989

Newly smitten Anthony Edwards overhears a phone call suggesting that a nuclear war has begun, and he has 70 minutes to live. Belonging to the small genre of films known as real-time action thrillers (see: Nick of Time (1995) and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope), Miracle Mile maintains suspense because we don’t know if the phone call was real and OH MY GOODNESS WHAT IF IT WAS? The movie hinges on an unforgettable moment and boasts a Tangerine Dream score, a haunting tone, and singularity bordering on eccentricity. Hemdale released Miracle Mile on only 143 screens, so you’ll be excused for not noticing it until it hit VHS… or really ever. 30 years later it’s a cult classic still struggling to establish its cult. It’s never too late to join.

JUNE

We’d been force-fed advance marketing and images of sequels and blockbusters and we knew it was all coming, like an avalanche of anticipation. And it was as big (maybe bigger) than we’d expected.

Ghostbusters II might have disappointed in 1989, but its biggest offense was just not being the original. The most surprising thing about Batman in light of the modern superhero renaissance? Tim Burton’s Batman is a political commentary on the dangerous power of the media to influence public thought. POW. Holy foresight, Batman! And would you be surprised to learn that Honey, I Shrunk the Kids outgrossed both Back to the Future II and Ghostbusters II? Released the same day as Batman, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids played for 16 weeks and earned a total of $130 million (but never reached #1).

And then there was Star Trek V: The Final Frontier – whatever that was. I don’t think I need to tell you, but JUNE WAS A REALLY BIG DEAL. Carpe diem the excuse to revisit all of these movies, including Dead Poets Society, obviously (released in 8 theaters on June 2).

And June wasn’t done yet – the month boasted a fifth release weekend. While Batman, Ghostbusters II, Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, and Dead Poets Society still held spots in the Top 5, Mr. Miyagi brought Daniel-son back for a third round with Karate Kid III, Dennis Quaid tickled the ivories as Jerry Lee Lewis in Great Balls of Fire! and Spike Lee left us a timeless joint.

DO THE RIGHT THING (Spike Lee) – June 30, 1989

After thirty years Spike Lee’s masterpiece retains every ounce of relevancy – and serves as a reminder about how little has changed. Provocative and moving, Do the Right Thing holds a mirror up to its audience to highlight the many and varied iterations of prejudice, systematic racism, and persistent injustice. Still controversial and inspiring contemporary study, Do the Right Thing should be required viewing for everyone that thinks movies like the Green Book have something interesting to say about contemporary race relations. Set during the hottest day of summer in a predominantly African-American community, tension and conflict increase until the steam valve explodes to release the pressure.

JULY

Even though the calendar finally turned, devoted cinema-goers would not get a reprieve from the onslaught on essentials. Even though the month saw only a handful of releases, included in those the much-anticipated sequel to Lethal Weapon, Timothy Dalton’s final and grossly underappreciated turn as 007, Meg Ryan’s public diner orgasm (“I’ll have what she’s having”), a slobbery pooch named Hooch, and two sleeper comedies that would each develop a devoted cult following. July of 1989 had it all – even if the world didn’t fully appreciate the Wheel of Fish in its moment.

WEEKEND AT BERNIE’S (Ted Kotcheff) – July 5, 1989

Do you remember what it was like to live in a world that would produce a movie about two working class stiffs who use their boss’ corpse like a marionette to avoid getting murdered? Do you remember what it was like when said movie could become a surprise box office hit? Anything could and did happen in mainstream Hollywood releases. Weekend at Bernie’s even contains suggested necrophilia! Still, it’d be the most charming movie featuring necrophilia you’ve ever seen.

The black-ish comedy contains legitimate wit and two affable co-stars in Andrew McCarthy and Jonathan Silverman that make even the most macabre jokes go down like a fizzy beach cocktail. Terry Kiser (Bernie) boasts a career lasting more than 50 years, but he’ll forever be remembered as Bernie Lomax. Critics wrote the film off as “tasteless,” but Weekend at Bernie’s would ride its modest box office success onto home video and a surprise sequel four years later.

UHF (Jay Levey) – July 21, 1989

Orion Pictures released UHF in the middle of July because it thought it had a potential blockbuster on its hands. Unfortunately, critics changed the channel on UHF, and the film faded to static after only two weeks. Time for a flex. I saw UHF twice in that limited theatrical window and thought, without any doubt, that the movie would surely become a success. Weird Al’s clever use of the UHF television station to create a playground for inspired parody, sketches, and bizarre vignettes keeps the gags firing, while injecting just enough narrative tissue to hold the outrageous film together. Quotable lines and indelible visual gags flow from the movie like water from a fire hose. “Red snapper. Very tasty!” “No more Mr. Passive Resistance. He’s out to kick some butt.” “Buy nine spatulas and get the tenth for just a penny.”

Every time I watch UHF I’m 11 again and watching it for the first time. Since 1989, the cult of UHF has grown, but the gap between those that love it and those who refuse to tune in to its frequency remains wider than Stanley Spadowski’s love of mops.

Elsewhere in July 1989…

As July came to a close, Tom Hanks carried Turner & Hooch to a $12 million opening weekend and Jason Voorhees headed to Manhattan for the 8th installment of the Friday the 13th franchise. Meanwhile Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade rode on, still clinging to the eighth spot on the charts in its 10th week of release. For a point of comparison, 2019’s Avengers: Endgame dropped out of the Top 10 after only seven weeks. The movies we loved hung around forever, defining our summers and becoming cultural fixtures. The question wasn’t whether or not you’d seen Indiana Jones or Batman – the question was: how *many* times have you seen them?

AUGUST

Ron Howard’s Parenthood, a thoughtful ensemble dramedy about the best and worst moments of nuclear-family life defined the month, even overshadowing a seismic shift in the way films would be made. Australian Yahoo Serious made his stateside debut in the affable (if rather unfunny) one-joke farce, Young Einstein. Sylvester Stallone found himself in the unintentionally comical prison drama Lock Up. The blockbusters and mega-hits continued to grace our multiplexes, but did the summer of 1989 have anything left to give?

THE ABYSS (James Cameron) – August 9, 1989

If you had a weakness for underwater thrills, 1989 was your kryptonite. The Abyss followed DeepStar Six, The Leviathan, the Roger Corman-produced Lords of the Deep, and the straight-to-video The Evil Below. The public’s mediocre response to The Abyss could be attributed to drowning in soggy thrillers. While most critics praised the “claustrophic” atmosphere and Industrial Light & Magic’s groundbreaking digital effects there was no shortage of complaints about the overlong, “dopey” ending. The Abyss, at its best, represents the unqualified vision of a director and a nexus for all future computer generated SFX. It’s the intersection of technological discovery and James Cameron’s H.G. Wells-inspired imagination. The Abyss dares to be a thoughtful, carefully wrought summer blockbuster that makes the audience ponder deep thoughts – a rare thing in 1989, but an extinct thing in 2019.

The family-oriented August successes continued with the release of John Hughes’ Uncle Buck – a sweet crowd-pleaser that sets John Candy’s well-intentioned (but domestically challenged) antics to Tone L?c’s beats. Perhaps best known as the movie that introduced most of us to Macaulay Culkin, Uncle Buck became a late-summer hit and inspired two failed TV series and even a Subcontinental remake.

After two weeks, Jason left Manhattan and New Line rushed Freddy Kreuger’s fifth Nightmare into theaters – where it was met with only slightly better reviews. Director Stephen Hopkins disowned the film after New Line and the MPAA “cut the guts out of it completely.” But it was a horror of a different kind that deserved a little more attention.

CASUALTIES OF WAR (Brian de Palma) – August 18, 1989

Quentin Tarantino has called de Palma’s Casualties of War “the greatest film about the Vietnam War.” Despite critical praise, audiences left the movie to perish in the jungle heat with a lowly $18 million gross. Like many other attempts to capture Vietnam on film, Brian de Palma concerns himself with the innate human barbarism unearthed by conflict. The film aims to immerse the viewer in the cruelty of war through the use of overtly artificial techniques rather than the simple amplification of reality. In many ways Casualties is more Apocalypse Now than Platoon, but even these comparisons to Coppola and Oliver Stone feel unfairly reductionist. De Palma has harnessed his tendency toward self-awareness to serve the nightmare story of Michael J. Fox’s PFC Max Eriksson rather than the other way around. This is a personal film and one that’s unfairly overlooked in de Palma’s filmography.

Elsewhere in August 1989…

As the dog days of summer hit their stride, Paramount dumped Richard Dreyfuss’ racetrack comedy Let It Ride into theaters without much of a promotional campaign. Loaded with wonderful supporting characters like David Johansen, Teri Garr, Jennifer Tilly, Cynthia Nixon, and Robbie Coltrane, Let It Ride undermines your expectations at most every turn by giving Dreyfuss’ everyman a day in the sun.

SEPTEMBER

The studio executive, clad in a dark trench coat, wanders into the dump. After glancing around to make sure nobody’s watching, he drops something and scurries off into the night like a cockroach. That something was the malformed mid-budget film that the studio had hoped to curate into a summer release. When the suits saw the finished product, however, they looked at each other with horror in their eyes and knew immediately what had to be done.

A September release doesn’t guarantee a lesser movie. It’s just as likely the studio doesn’t understand how to sell it to a mass audience. School’s back in session, and audiences have drifted away from the multiplex. September’s duly earned its reputation, but the month also produces a number of entertaining eccentrics that just didn’t fit easily into genre conventions.

SEX, LIES AND VIDEOTAPE (Steven Soderbergh) – August 18, 1989

The date says August, but I’m including Soderbergh’s breakout movie in the September slate because that’s when Miramax expanded its indie darling into 347 theaters – a number which might not seem like much considering that The Last Crusade opened on 2,327. To fill in the backstory, let’s rewind to January 22, 1989.

Sex, Lies and Videotape debuted at the U.S. Film Festival in Park City, Utah (Robert Redford would rechristen it Sundance a couple years later). The scandalously-titled (but only mildly tawdry) drama caused so much buzz that by the time of its final screening, tickets had become currency. Redford, Sidney Pollack, and Rain Man producer Mark Johnson were all clamoring to produce the next Soderbergh picture.

In 1989, Park City successes just didn’t get that kind of attention. A pair of greenhorn movie producers made a desperate pitch and outbid ten other potential distributors for theatrical rights. Those “ruthless” bidders were, of course, Bob and Harvey Weinstein, and Sex, Lies and Videotape became Miramax’s first big win. Soderbergh and Miramax refashioned the entire indie landscape, blurring the line between the studios and the indies. Bob and Harvey expanded Sex, Lies and Videotape into 500 screens across the country, inserting it into theaters recently vacated by Batman.

Audiences may have been lured by its sensationalistic title, but Soderbergh’s breakout was a modest four-person, dialogue-driven movie about sex and relationships and the terrible ways that people use intimacy as a weapon – all without the suggested voyeurism. Straddling black comedy and heavy drama, Sex, Lies and Videotape retains its potency – due in no small measure to James Spader’s delicious performance – and stands out as the catalyst of the independent boom of the 1990s.

THE BIG PICTURE (Christopher Guest) – September 15, 1989

Despite positive reviews, Columbia dumped Christopher Guest’s Hollywood satire into three screens before sweeping it onto home video. David Puttnam, president of Columbia Pictures, greenlit the project but was fired two weeks into production. The new regime felt they were the target of The Big Picture’s brutal satire – which speaks to the accuracy of Guest’s portrayal and also happens to mirror the same process that turned Steven Soderbergh into an overnight success.

Aspiring writer/director Nick Chapman (Kevin Bacon) wins a student film contest and Hollywood bigwigs desperately want to make a deal with the young auteur to make his dream project. The dream project becomes a nightmare when (stop me if you heard this somewhere before) a new studio head steps in and cancels it. Based on Columbia’s disavowal of the project, it might suggest that The Big Picture comes off as some kind of lascivious insider tell-all, when in fact it’s a warm comedy with film-within-a-film segments that detour into surreality. The supporting cast includes J.T. Walsh, Michael McKean, Jennifer Jason Leigh, and some fantastic one-off cameos, but it’s Martin Short’s uncredited turn as Nick’s frazzled agent that belongs in one of the all-time great comedy performances.

SEA OF LOVE (Harold Becker) – September 15, 1989

Released the week before Ridley Scott’s Black Rain, the two competed for the same adult-thriller audience. As a result, both became relative successes, but neither left much of a lasting impression. If you haven’t seen Black Rain, watch that one as well (Michael Douglas and his dead-eyed gaze demands it), but it’s Sea of Love that stands out as the best representative for that anything-goes September release mentality.

Based on a screenplay by Richard Price, Sea of Love marks Al Pacino’s first film in four years after the disaster that was Revolution (1985). Despite solid scripting, plotting, and entertaining performances from Pacino and vamp Ellen Barkin, fans are often hesitant to admit their affection for Sea of Love, like the film belongs to some kind of cultish and unsavory underbelly of mainstream cinema. Becker’s serial-killer thriller knowingly plays with Film Noir conventions and conscripts them into a thoroughly modern genre film that also touches on existential loneliness and mid-life crises. John Goodman co-stars as Pacino’s investigative partner and provides some welcome comic relief. It might feel like a guilty pleasure, but Sea of Love joins a storied tradition of steamy 1980s potboilers born out of the embers of Film Noir.

As the late-season movie-going stragglers stumbled out of the multiplex and into the glaring low-slung sun, they checked their watches and wondered where all the time had gone. And in the moment when the post-summer malaise might have hit home, they realized that in only two months they’d be back in line to see the first of two long-awaited sequels to Back to the Future. They inhaled, allowing the suddenly crisp air to fill their lungs, and knew that it was a great time to be a moviewatcher.